The second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic has shone a painful spotlight on the dire conditions of tea garden workers struggling against poverty in India.

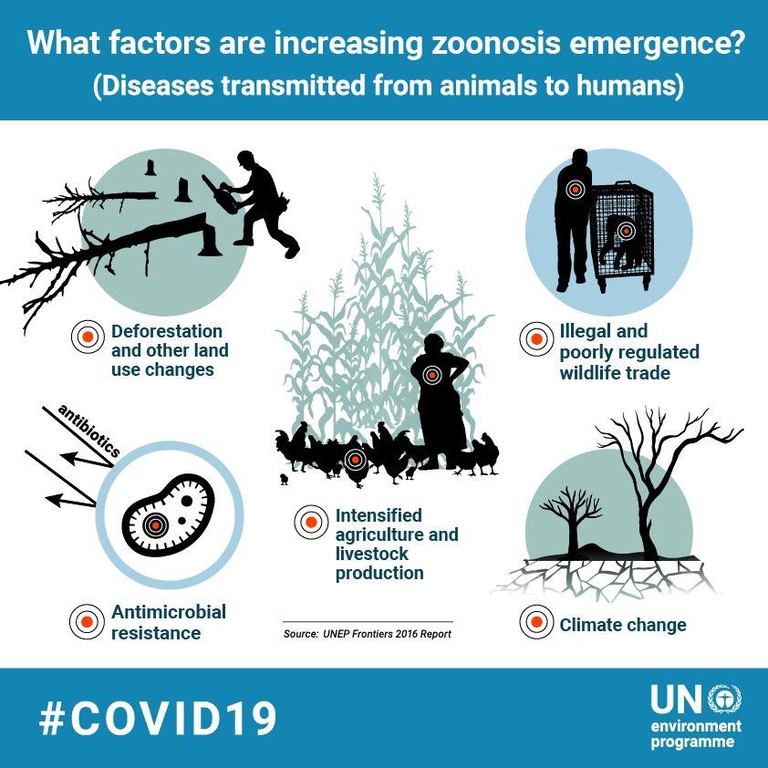

Factory farming conditions and antibiotic-resistant pathogens emerging as a result of them pose an existential threat to humans in the form of zoonotic diseases. Why it’s time to produce and consume food more thoughtfully.

Much has been written about the coronavirus and how people can prevent being exposed to it, including through social distancing and good hygiene. It’s now vital to get to the root cause of this pandemic and focus on primary prevention so as to avoid another, perhaps even harsher, outbreak. While the illegal wild animal trade and wet markets have been singled out, factory farming of animals in general is much less discussed. More attention needs to be paid to its public health risks – before it’s too late.

Animals can sometimes carry harmful germs like viruses, bacteria, parasites and fungi that spread to people and cause illnesses which are known as zoonotic diseases or zoonoses. Around 60 per cent of all known infectious diseases in humans are of this type, as are 75 per cent of emerging ones according to a 2016 UN report.

For example, wet markets are commonplace in many countries including China, India, Vietnam and in other parts of Southeast Asia; they sell fresh meat or fish, often (though not always) killed on demand at roadside slaughterhouses, and many, though not all, sell wild animals. This way, domesticated animals not only get viruses from the wild animals that are also sometimes sold in these markets (this is thought to have happened with the novel coronavirus) but can also become carriers and spreaders of diseases originating due to the filthy conditions they’re kept in, as in the cases of bird and swine flu.

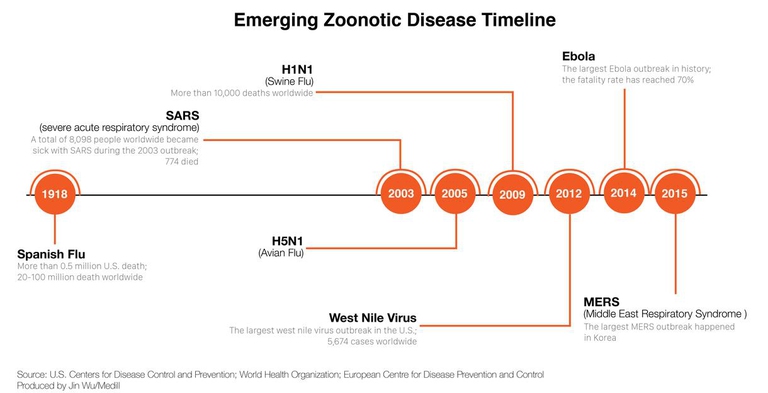

As Covid-19 joins the list of zoonotic diseases, the world has already seen millions of deaths in the past due to the consumption of and contact with animals. Starting with three pandemics that have emerged since 2000, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, swine flu (H1N1) in 2009 and now the disease Covid-19 caused by the virus Sars-CoV-2: evidence suggests the latter has come from animals, as did SARS which spread from civet cats and bats in China, whilst animal to human transmission of swine flu first took place in an intensive pig farm in Mexico.

Other than these, there have also been outbreaks of bird flu (avian influenza) from poultry, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) first transmitted from camels, Ebola from monkeys and pigs, Rift Valley fever from livestock, West Nile fever from birds, Zika from monkeys and Nipah from bats and pigs. The human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, is widely thought to have originated from the consumption of bush meat. Incidentally, avian influenza continues to mutate and wreak havoc in poultry farms around the world including in Germany, China, India and the UK, and an outbreak of African swine fever (ASF) was reported in Poland recently.

Read more: Ebola exists. A day at the heart of the epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Although some zoonoses are probably unavoidable as these viruses have always been present in wildlife, much human suffering resulting from them could be avoided by changing the way people come into contact with animals. In particular, by establishing a more balanced and respectful relationship with other living beings.

Read more: Ilaria Capua. To the coronavirus we’re just another host animal, so let’s use our intelligence

There’s clearly a link between the emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses and intensified poultry production systems.Marius Gilbert, spatial epidemiologist at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

Our demand for meat and other animal products means that huge numbers of animals such as cows, chickens and pigs are crammed together in crowded, faeces-ridden farms, transported in filthy lorries, and slaughtered on killing floors soaked with blood, urine, and other bodily fluids – the perfect breeding grounds for pathogens. Public health experts have been ringing the alarm about zoonotic diseases for years. Among these is Doctor Michael Greger, author of the book Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching, who says factory farming is a “perfect storm environment” for infectious diseases.

In a video (above) that first appeared more than a decade ago, Greger states that there have been three eras of human disease: first, that of domestication, when we brought wild animals to barnyards who in turn brought diseases with them; the second started in the 18th and 19th centuries with the Industrial Revolution, leading to epidemics of the so-called diseases of civilisation – diabetes, obesity, heart disease, cancer, etc; and finally, the third era of human diseases started about 30 years ago due to land use and agricultural intensification.

“About half of the egg-laying hens on this planet are now confined in what are called battery cages,” he points out. “In these small barren wire enclosures extending down long rows and windowless sheds there can be up to a million birds on a single farm. About half of the pigs on the planet are crowded into these intensive confinement operations. These intensive systems represent the most profound alteration of the human-animal relationship in 10,000 years”. In words that seem prophetic now, he concludes by saying: “The next pandemic may be more of an unnatural disaster of our own making. A pandemic of even moderate impact may result in the single biggest human disaster ever [and] has the potential to redirect world history”.

A 2004 joint consultation of the World Health Organisation (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE, the world’s leading veterinary authority), concluded that “anthropogenic factors such as agricultural expansion and intensification to meet the increasing demand for animal protein” are one of the major drivers of zoonotic disease emergence.

Given such warnings, it may come as a surprise that policymakers haven’t taken them seriously enough to enforce sufficient preventive measures. In fact, as an editorial in the American Public Health Association journal observes: “It’s curious, therefore, that changing the way humans treat animals – most basically, ceasing to eat them or, at the very least, radically limiting the quantity of them that are eaten – is largely off the radar as a significant preventive measure … Failure to think ahead can’t repeatedly be excused”.

In addition, animals on factory farms are routinely fed vast amounts of antibiotics in order to keep them alive in conditions that would otherwise kill them. Because of this, even the most powerful antibiotics aren’t effective against certain bacteria, contributing to the emergence of “superbugs” – new, aggressive, antibiotic-resistant pathogens. According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an estimated 80 per cent of all antibiotics produced is sold to livestock farms, and a 2019 study documents how the growing demand for animal protein resulted in a tripling of the occurrence of antibiotic resistance in disease-causing bacteria in livestock between 2000 and 2018.

In the US, a person dies every 15 minutes because of an infection that antibiotics can no longer treat effectively, a total of 35,000 deaths per year. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), antibiotic resistance is “one of the world’s most pressing public health problems,” and other experts predict that at the current rate, more people will die of diseases caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria than of cancer by 2050.

Just as humans are more likely to succumb to disease when we’re stressed, weakened or wounded, these same factors also suppress the immune systems in animals, leaving them extremely vulnerable to catching new infections. As a result, the worldwide animal trade creates very sick animals and ideal conditions for pathogens to multiply and jump from animal to animal, and ultimately to humans. To prevent the next pandemic, we need to look beyond the wet markets or illegal trade in China.Aysha Akhtar, neurologist, public health specialist and author, US Public Health Service Commander and Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Fellow

The ultimate culprit are our patterns of animal consumption. Yet the re-opening of Chinese wet markets and bizarre promotion of bear bile as a coronavirus antidote beg the question about how serious the world really is about taking this crisis head-on. However, there are some positive signs.

The consumption of vegan products has increased exponentially and according to a report by Allied Analytics LLP, the global vegan food market, valued at 14.2 billion US dollars in 2018 will reach 31.4 billion in the next five years. China is already beginning to demand safe, reliable and healthy food and companies like US-based Just, which makes plant-based egg products, are fielding a wave of inquiries from Chinese food companies. An online petition urging the WHO to shut down live-animal meat markets has surpassed 100,000 signatures.

Read more: Veganism in India, how the dairy-loving country is embracing a plant-based diet

Also, given the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, through collaborative networks like the FAIRR initiative investors are increasingly assessing their investee companies’ readiness to operational risks through the animal welfare standards set by the Business Benchmark on Farm Animal Welfare.

Read more: Animal welfare, how investors are abandoning factory farming

As David Benatar writes in the editorial Chickens Come Home to Roost, “it’s time for humans to remove their heads from the sand and recognise the risk to themselves that can arise from their maltreatment of other species”. If all stakeholders in society – be it investors, consumers, governments or food manufacturers – fail to rethink their business-as-usual practices and work towards a new normal, Covid-19 will likely not be the last pandemic that humankind witnesses, and perhaps not even the deadliest. And just like the effects of climate change, the poor and vulnerable will be the worst affected.

Read more: India’s coronavirus lockdown causes deaths among migrant labourers forced to return home

We have the power to decelerate the emergence of new zoonoses. Or even reduce the harshness of the next outbreak. If we have the will to shut down entire societies for weeks on end, something that would previously have been considered extreme and “not an option”, surely we have the will to change our diets and global food system. Until we don’t go all the way in preventing the spread of these viruses by outlawing unsanitary live-animal markets, questioning the factory farming model at its core and creating awareness around food choices – therefore, until all animals aren’t treated better – zoonotic diseases will likely continue to resurface. Ultimately, it’s time to stop wilfully spinning this pandemic roulette.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

The second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic has shone a painful spotlight on the dire conditions of tea garden workers struggling against poverty in India.

In response to a lack of public services, organisations and individuals are helping citizens weather the devastating Covid-19 crisis in India.

A study indicates that the zoonotic origins of coronavirus may have been favoured by global warming’s impact on the conditions for bat habitats.

While Africa’s Covid-19 response has been praised by some, the pandemic has triggered the continent’s first recession in 25 years.

In Coronation, a documentary filmed by the people of Wuhan, the dissident Chinese artist documents the government’s rigid control during lockdown.

David Nabarro of the WHO analyses worldwide actions against the pandemic. Lockdowns alone aren’t a sustainable response to stopping Covid-19.

Kenya may fail to meet its target of ending female genital mutilation by 2022 as Covid-19 school closures have seen more girls undergo the illegal practice.

Helsinki Airport has begun implementing a Covid-19 test which is both noninvasive and simple. The exceptional nurses involved are dogs.

The drop in air pollution during worldwide lockdowns helped prevent thousands of premature deaths. But the situation is returning to pre-crisis levels.