The tribes of the Lower Omo Valley in Ethiopia live in close contact with nature and the river they depend on. But their ancestral ways of life are being threatened by the impacts of a mega-dam, climate change and a booming tourism industry.

Antinatalism advocates for people to have fewer or no children and is bringing the issue of overpopulation into the environmental debate. A definition of this philosophy as well as the arguments for and criticisms against it.

When talking about solutions to climate change, we mainly focus on fossil fuel reduction, changes in transportation, minimising consumption and dietary choices, just to name a few. But one often overlooked aspect is the impact of overpopulation. This has contributed to a resurgence of antinatalism, a philosophical position and social movement whereby people choose not to procreate, in particular for environmental reasons. The notion that having children may be a bad idea for the environment seems to be gaining mainstream popularity, especially through social media.

Antinatalism assigns a negative value to birth. Adherents of this philosophy (antinatalists) view life not as a miracle but as resource guzzler on an already over-burdened planet. This argument arises most often in relation to the climate crisis: people are worried about bringing children into a world threatened by rising seas, mass displacement, resource limitations, human encroachment on natural habitats and meteorological calamities. While other reasons lead people to embrace this ideology, such as a will to reduce suffering, the absence of a child’s consent to being born and breaking away from the forced obligation to carry on one’s lineage, in this article we will delve into its environmental underpinnings.

Some of the earliest formulations of the idea come from Ancient Greece: South African philosopher David Benatar quotes the Greek tragedian Sophocles and the text of Ecclesiastes in his book Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence. Buddhist teachings dating back to 400 BCE state: “Oblivious of the suffering to which life is subject, man begets children, and is thus the cause of old age and death. If he would only realise what suffering he would add to by his act, he would desist from the procreation of children; and so stop the operation of old age and death”. Therefore, the sentiments at the heart of antinatalism have been around for a long time.

However, in modern history we can trace the proliferation of discussions around procreation and (over) population to the 18th-19th century when Thomas Malthus sounded the alarm with his Malthusian theory, according to which population pressures would outstrip food supply. More recently, in 1968, University of Stanford biologist Paul R. Ehrlich published the bestselling book The Population Bomb, written together with his wife Anne, arguing that the growth in global population would lead to mass starvation, societal upheaval and ecological deterioration. Along these lines, the reasons behind people voluntarily choosing not to procreate, or having fewer children, in the present age have become embedded in a wider environmental discourse especially in relation to climate change.

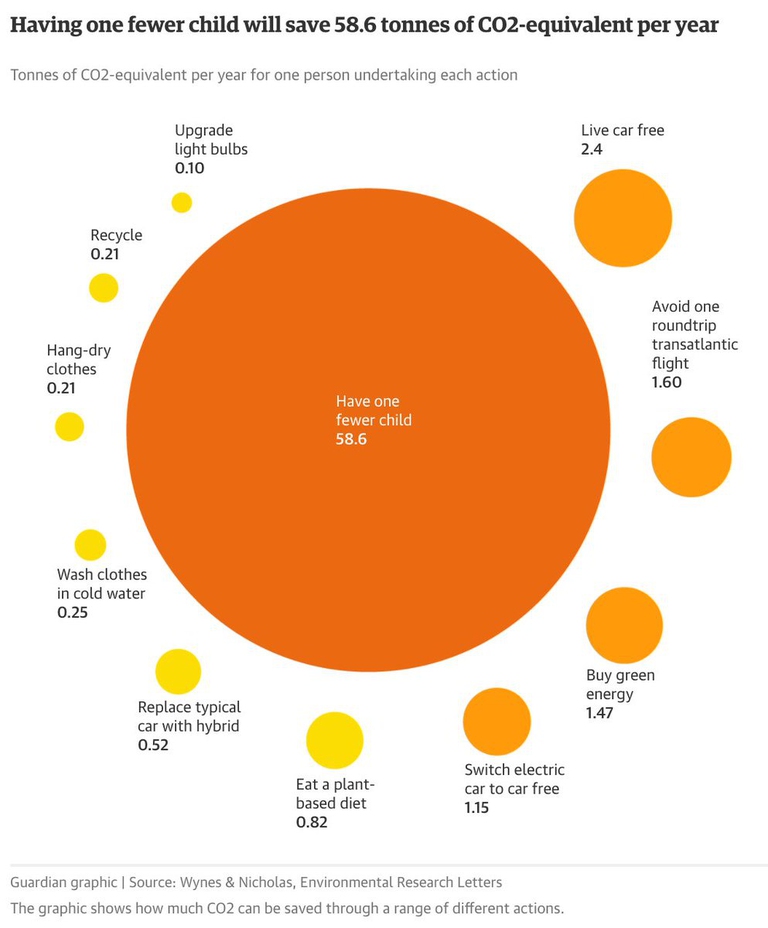

A 2017 study sets out the positive environmental outcome of different actions such as selling one’s car, avoiding long flights and eating a plant-based diet. It finds that by far the biggest impact is determined by having one fewer child, equating to a reduction of 58 tonnes of CO2 for each year of a parent’s life. By comparison, living car free for a year saves 2.4 tonnes. While over-consumption is another side of the population coin (in the United States, a person is responsible for 40 times the emissions produced by a Bangladeshi), the impact of overpopulation on the planet can’t be ignored.

Climate activists are also concerned about inflicting the ecological state of the world of today – and especially of tomorrow – on a child. In less than 100 years, the world’s population has nearly quadrupled, rising from two billion in 1928 to over seven billion in 2019. In a world where water-related conflicts, resource depletion and biodiversity loss – all accelerated by the rate of human consumption – are already a reality, antinatalists express uncertainty in being able to ensure a habitable planet to newborn children.

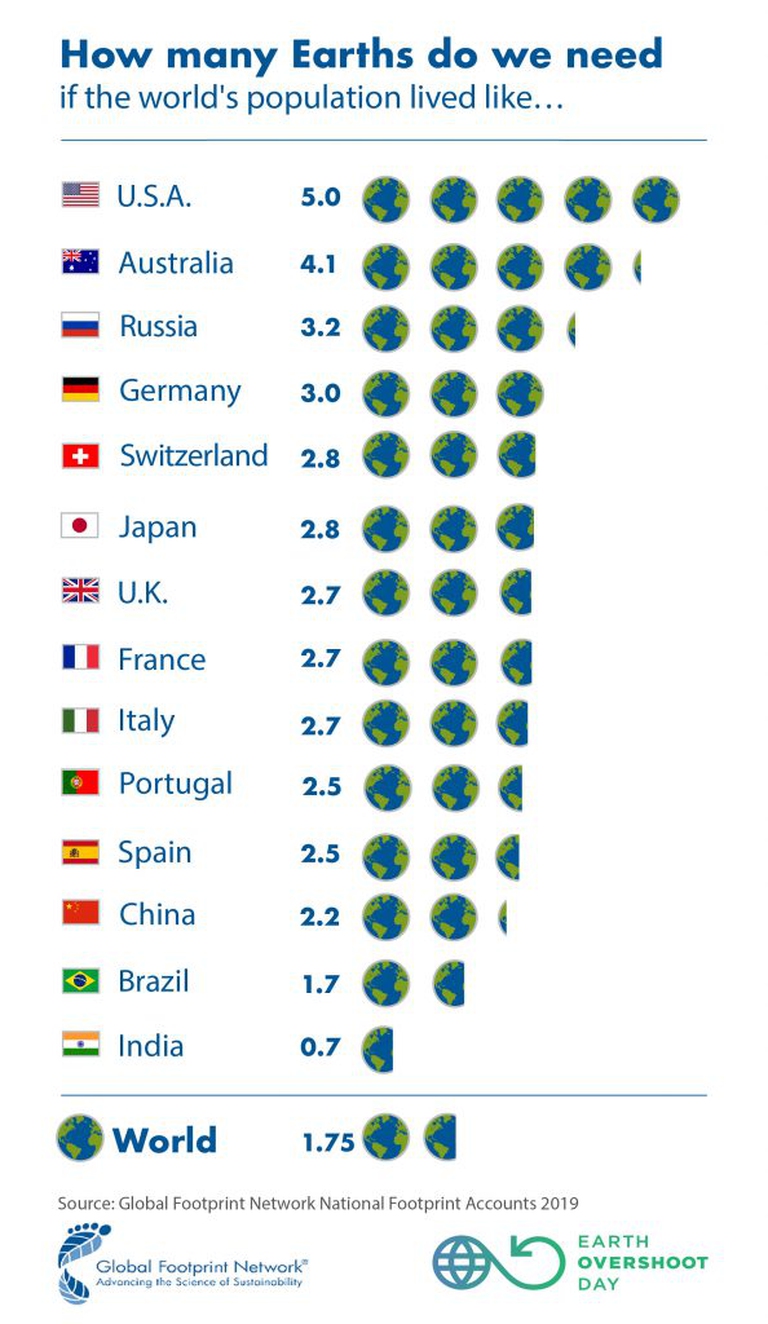

According to calculations by the Global Footprint Network, Earth Overshoot Day took place on 29 July in 2019 – the earliest it’s ever been since the 1970s, when we started using more than what our planet could support in a year – meaning that by that day humanity had already used up its annual allowance of water, soil, clean air, as well as other resources. Humanity currently consumes 1.75 Earths every year.

While countries like India, China and Brazil have lower per capita consumption levels, the impact of the climate crisis and resource depletion is going to hit them – especially the poorest of the poor – the most, together with other developing countries around the globe. To raise awareness about this and bring the concept of antinatalism into the mainstream, some Indians are taking the lead. For instance, in February 2019, 27-year-old Raphael Samuel announced plans for an unusual lawsuit: against his parents for giving birth to him.

“It was not our decision to be born,” he told the BBC. While Samuel says he’s actually close to his parents, his complaint is more fundamental: he believes it’s wrong to bring new people into the world without their consent. He decided to try and sue his parents for a symbolic amount of money, such as a single rupee, “to instill that fear among parents in general. Because now parents don’t think before having a child”. Remaining in India, Bangalore also saw its first national meet of antinatalism proponents in 2019, a support group for those who wish to be child-free in a tradition-heavy country like India.

It’s unethical to have children in a world that is facing another mass extinction and unprecedented climate change. It’s selfish to think about your own tiny family and not the world in these times. It’s stupid to create life and leave it to fend for itself in a hostile and rapidly changing world. India is populated enough, it’s time it goes on a birth strike for its own good.Neera Majumdar, Journalist

Like the fear of nuclear annihilation during the Cold War, as well as the fact that Malthus’ predictions of impending food shortages haven’t occurred on a global level, could technological advances and political will prove that antinatalists’ fear of planetary boundaries and overpopulation is exaggerated? While one can hope for the best, this hope is precariously placed on young people‘s shoulders, as they’re also the future scientists and engineers needed to develop the technological solutions to global warming that are still unavailable. Antinatalists would argue that this amounts to a “greater good” argument for procreation, in which future children are seen as a means to an end, i.e. our overall welfare, rather than being concerned with their individual well-being.

On the other side of the coin, many countries pride themselves of the demographic dividend ratio, whereby the share of the working age population is larger than that of people not of working age, leading to a great economic contribution, therefore growth. Instead, fewer young people as a result of declining birth rates means a higher proportion of an ageing population, which needs to be taken care of by the state, burdening taxpayers and national revenue. The concern is such that some countries with low birth rates are adopting incentives for people to have children, including financial ones, such as Greece offering a 2,000 euros (2,200 US dollars) baby bonus. These arguments are what led the Chinese government to abandon its one-child policy, an anti-natal measure adopted for over three decades.

Demographers warn that China’s population will begin to shrink in the next decade, potentially derailing the world’s second-largest economy, with a far-reaching global impact. By 2050 as much as a third of the country’s population will be made up of people over the age of 60, putting severe strain on state services and the youth who bear the brunt of caring for elderly relatives. Furthermore, environmental journalist David Roberts notes that where you find concern about overpopulation you often also find racism, xenophobia or support for eugenics (the practice or advocacy of improving the human species by selectively mating people with specific desirable hereditary traits) lurking in the wings.

A balance must therefore be struck, a view reiterated by a major study published in January conducted by an international group of 11,000 scientists that concluded that the world needs to stabilise its population and gradually reduce it — within a framework that ensures social integrity, such as respect for human rights, which are instead violated by the dictatorial impositions embodied in the Chinese one-child policy. Focusing on female empowerment, including girls’ education, financial independence for women, as well as encouraging knowledge and access to family planning, could be one of the most powerful levers to bend the population curve, therefore reduce emissions and resource depletion.

Read more: The role of women and gender in the fight against climate change

The sixth mass extinction and ecological collapse is looming upon us. At a time where every small step counts towards helping the survival of humans on the planet, having fewer children is a matter of preference and may be one way people can contribute to reducing their impact, among the many other actions that can be taken. The aim, in any case, remains the same: to avoid leaving a planet unsuitable for tomorrow’s children.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

The tribes of the Lower Omo Valley in Ethiopia live in close contact with nature and the river they depend on. But their ancestral ways of life are being threatened by the impacts of a mega-dam, climate change and a booming tourism industry.

Education Minister Lorenzo Fioramonti has announced that the topics of climate change and global warming will soon be taught as subjects in Italian schools.

Come le famiglie di una delle aree più aride del Myanmar coltivano gli ortaggi utilizzando sistemi che usano l’acqua in modo efficiente, risparmiandola. Tra questi c’è anche un progetto di Terres des Hommes Italia.

The European Parliament has voted in favour of the European Citizens’ Initiative My Voice, My Choice, calling for safe and accessible abortion across Europe. The next step now lies with the European Commission, which is expected to develop concrete measures.

Montevideo’s Senate has passed a new law allowing ‘death with dignity’ (but not assisted suicide), with the procedure permitted even just a few days after the request.

Obamacare, free trade agreements, LGBT rights, immigration, and climate change were the main targets of Donald Trump’s first day in office at the White House.

KBK is the short form referring to the region comprising the Kalahandi, Bolangir and Koraput districts of India’s eastern state of Odisha. News on acute poverty leading to child-selling and starvation deaths in the region prompted Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to visit these districts in the 1980s and inaugurate several poverty alleviation schemes. None of

Una ventina di ragazzi ha denunciato le politiche ambientali del governo Usa: «Non fa abbastanza per il clima e dunque non ci protegge».

Disasters caused by climate change bring many Indian families to their knees, reaching extreme poverty levels. Condition that leads mothers and fathers to put their children in human traffickers’ hands, making them work illegally or forcing them in the prostitution racket. This dramatic situation has been revealed by the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize Kailash Satyarthi,