As per tradition after 12 years India held Mahakumbh, the world’s largest spiritual congregation that has been attracting pilgrims from across the globe.

“The defence of human rights can’t be left solely to those who’ve experienced violations firsthand”. The sons and daughters of Sesto San Giovanni – a place synonymous with resistance, from which hundreds of political opponents were deported – are fighting for the memory of the victims of Nazism and Fascism. An exclusive reportage from Italy.

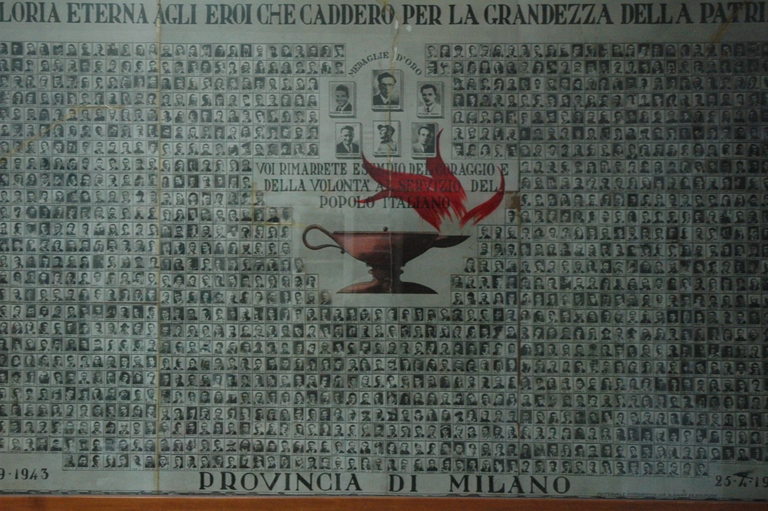

Hundreds of small faces form a black-and-white mosaic encased in an oak frame, which covers an entire wall. Almost all the faces are young, many belonging to people at the start of their adult life. These are the deportees who worked in the industrial area of Sesto San Giovanni, on the outskirts of Milan – one of the largest in Italy. These political prisoners were captured because they took part in strikes between 1943 and 1944, during WWII, against Benito Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship and Adolf Hitler’s Nazi occupation. On average, they were 33 years old. Along the staircase at the local chapter of the National Association of Former Deportees (ANED, Associazione Nazionale Ex Deportati), one can’t help but stop to look at the faces peering from behind the glass, often smiling. They could easily be posing for a passport photo. There’s a simple elegance to the men, almost all of whom are wearing a shirt and jacket. All the women wear their hair up, except for one whose wavy locks fall almost to her shoulders. Her lively eyes and smile are those of a teenager.

“Right after the war, the antifascists came to our house to ask for a picture of my father. They wanted to re-establish order in the chaos that the conflict had wrought. There he is. He was a labourer and a violinist, you know? He even spoke German because he’d worked in Germany”. These are the words of a man in his eighties, the president of what’s commonly known as Deportee House (“Casa dei deportati”) in Sesto. His name is Giuseppe Valota; his father Guido died in the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Like most people from the area who died in the camps, he’d taken part in strikes in 1943 and 1944 in which political opponents were repressed by the fascist regime. Guido worked for Breda, a group of companies operating in steel-making, engineering, shipbuilding and the military. Striking meant halting the production of firearms and military vehicles.

A faint light shines into the basement in which ANED Sesto has held its meetings since the late 1970s. Nearby Villa Zorn was used before then. In 1946, war widows convinced survivors – scarred and traumatised, both mentally and physically – to create a place in which to meet. Together, they worked through their pain and kept the memories of their loved ones alive. Giuseppe’s own mother, Melania Gervasoni, probably passed this desire onto her son at a young age.

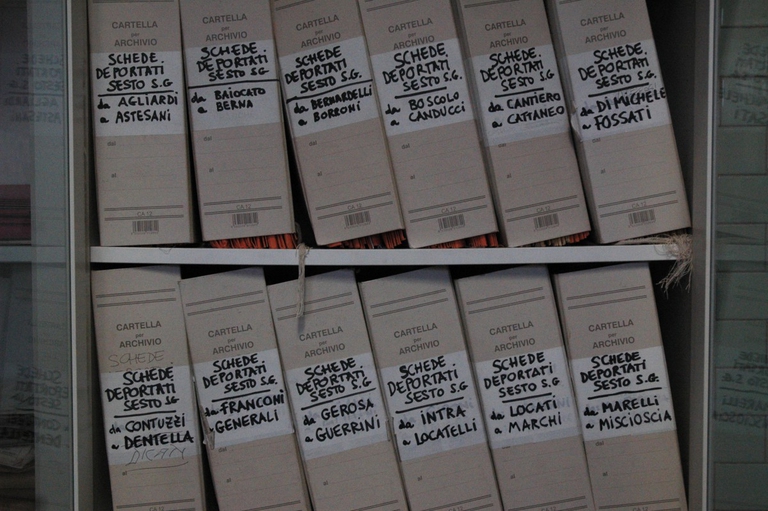

Starting in 1995, Valota embarked upon an extraordinary investigation. The retired electrical engineer began interviewing all the survivors of political deportation in Sesto San Giovanni’s industrial district, as well as their families, on his own, without remuneration or formal training. In his two-room flat in Via Giardini at number 14, he interviewed about 50 former deportees and 99 of their relatives. Finally, after half a century, a better understanding of what had happened began to take shape and an archive was born. This led to more precise estimates of the number of political opponents – the so-called “red triangles” – who were sent to the camps: 577 deportees, 233 of which lost their lives, leaving 344 survivors. Of the 13 women who were deported, every single one survived and returned home after the war.

“I started coming to ANED in the early 1990s because I had more free time,” Valota recounts. These days he’s cataloguing information about six more deportees. “I wasn’t a historian, but I wanted to know more. Many of the survivors were still alive and – not without a certain embarrassment – I started asking them questions: How many deportees came from Breda? How many from Falck? How many died? How many came back? But no one was able to tell me. I was shocked. How can this not be known? So I told myself: I’ll do the research”.

With the verve of a journalist and persistence of an academic, over the past 25 years Valota has published two books, Dalla fabbrica ai lager (“from the factory to the camps”) and Streikertransport. He has also given lessons in schools and accompanied students to former concentration camps. His work has sparked other collaborations. Other ANED members, several associations, teachers and volunteers have all given a helping hand. Director Renato Sarti created a theatre piece inspired by his research that has been staged in various theatres, including Milan’s prestigious Piccolo Teatro. Giuseppe has given the 577 deportees their voices back. And there’s more: “First of all I interviewed my mother, Melania. Family members left behind represent another aspect of deportation: the waiting, loneliness, pain; the decades without answers. No one had ever thought about the wives or the children like me”.

It’s almost midday, but we haven’t yet addressed the reason why we first met at a press conference a few months ago. Last June, Sesto San Giovanni’s council put some buildings up for sale without warning. Many of these housed spaces rented by various organisations and charities, including ANED, Ventimila Leghe, Auser, AVIS, Anmil, Maestri del Lavoro, Freecamera and CAI. The Council appealed to financial reasons to justify this decision, which followed the election in 2017 of the first centre-right administration in Sesto in 72 years. In fact, the council – led by Forza Italia’s Roberto Di Stefano with a majority that also includes members of parties further to the right, such as The League, Brothers of Italy-National Alliance and the Italian Liberal Party – is threatening to clear out buildings that citizens go to for important services and that have become symbols of community gathering, rights campaigning, solidarity and antifascism.

“After the first eviction hit Ventimila Leghe, an association that helped us organise the Viaggi della memoria (‘remembrance journeys’), I was expecting this to happen to us too,” Giuseppe comments. “The Sword of Damocles is undoubtedly hanging above our heads, however, we can stay here for two more years. If no prior warning is given, the contract will be renewed even if it’s almost expired. We live in hope and meanwhile, I keep working”.

We hear a “hello” coming from the stairs. As promised, Raffaella Lorenzi has joined us. This 84-year-old former primary school teacher is the daughter of a deportee, Cesare, whose name was given to one of the streets in the old Falck metalworks district. Her voice is low because she has just spoken at a memorial event. Nevertheless, Raffaella wants to speak her mind with all the strength she has: “When I learned this place was being put up for sale, I was overcome by anguish and rage. I wrote to the mayor that ANED is our family. We reconstructed our fathers’ stories here. I asked him: ‘Why are you doing this? For your own interests or to erase the memory? Let us know either way’. I never heard back”.

In 2018, the municipal council cut funds for school trips to former concentration camps by 70 per cent. In 2019, Ventimila Leghe and ANED were forced to resort to crowdfunding to raise enough money. “We made it thanks to donations from civil society,” Raffaella continues. Every year, she meets an average of 500 students. “I tell them my father’s story,” she explains.

Cesare Lorenzi worked at Falck Concordia as a specialised mechanic. He came to Sesto from Piombino, in the province of Livorno, in Tuscany, and had been a socialist and antifascist from a young age. In 1922, the year Mussolini took power and began to establish the fascist regime, Cesare was tortured and unjustly imprisoned in the Tuscan town of Volterra. Subsequently, in Sesto he became the treasurer of the clandestine group Soccorso Rosso (“red rescue”), which supplied food and money to the families of prisoners, exiles and deportees. The fascists arrested him after the 1944 strikes, together with Guido Valota, Giuseppe’s father.

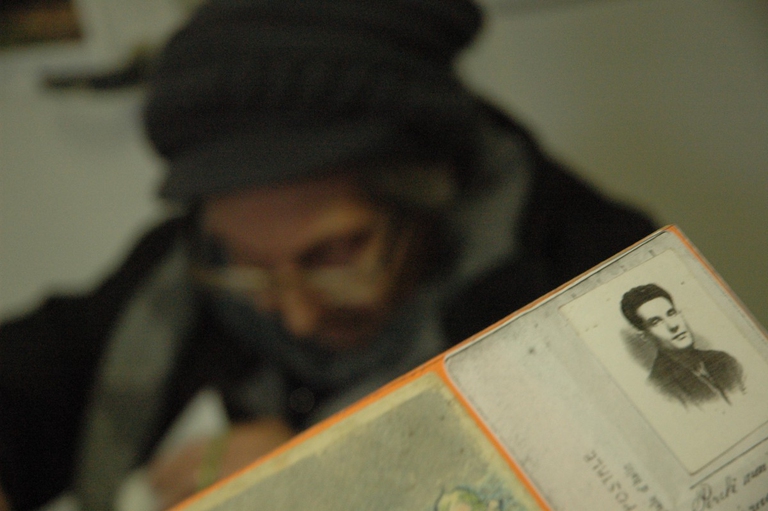

At that point, Raffaella was only nine years old and was forced into a desperate and daring search together with her mother: “Having been displaced in Brianza (the area north of Milan, ed.) my mother took her bike and the tram to the police precinct in Sesto, but they didn’t have any information. Someone told her Cesare was at the barracks in Palazzo Marino in Milan, where the fascists held their prisoners. They told her she could take something to eat and a change of clothes. So we left together to try and find him. We ended up in a basement below what is now Milan’s city hall. The room was dark, I remember only a faint light. There were three chairs and a soldier with his rifle slung over his shoulder. When my father came in, I saw his black hair had turned white. After many years, I learnt that his jailers had staged his (fake) execution by firing squad”.

Raffaella looks at the picture of her father. Like him, she has big, clear eyes, and strong facial features. “Afterwards, we returned to Brianza. The journeys were risky because of bombings, broken or derailed trams and sirens. Then, one day my mother went back to Milan and he was no longer there. They told her to go to Hotel Regina, near Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, where the Nazi SS forces were based. She was kicked out. She tried in San Vittore prison but he wasn’t there either. A man found a note with our address on it: ‘They’re taking us to the Umberto I barracks in Bergamo’. We got on a women’s bike, me crouching on the frame. But he wasn’t in Bergamo. A relative told us that a freight train was leaving from Brescia. We went there, crossed the tracks. The train had come to a standstill in the countryside. Women were carrying bags in which bottles and bread were visible. My mum started knocking on every carriage, shouting ‘Lorenzi’, until my father looked out. A young German soldier let him off the train”.

“He tried to reassure us: ‘They’re taking us to Germany to work. It’s better this way, San Vittore is more dangerous. They kill ten Italians for every German that is taken in the city’. I kissed him and hugged him. ‘Soon the war will be over and I’ll come back to you’, he said”.

“Then he got back on the train; smiling, with a glass in his hand, he shouted: ‘Viva l’Italia’ (long live Italy). I saw similar scenes in Life Is Beautiful (La vita è bella), Roberto Benigni’s Oscar-winning film,” Raffaella concludes. Her father, the 41-year-old of unwavering ideals, died in Mauthausen on the 22nd of May 1945, succumbing to tuberculosis and malnutrition.

Sesto San Giovanni is a symbolic city in Italian history, one of great industry and a stronghold of antifascist opposition, many of whose inhabitants fell victim to deportation. Subsequently, in the postwar era it became a place of reconstruction in which the political left was deeply rooted. A symbol of popular organising. It’s no coincidence that Sesto San Giovanni was awarded the Gold Medal of Military Valour in the fight for the liberation from Fascism. Deportee House isn’t far from city hall. All over the city there are monuments commemorating war victims, deportees and the partisans (“partigiani”) of the Italian resistance movement. However, not only has the new centre-right mayor never visited ANED or its archive and has allowed its headquarters to be put up for sale, but he also refused to grant honorary citizenship to Liliana Segre, senator for life, who was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau as a child because she was Jewish.

Di Stefano declared that “Segre isn’t part of Sesto’s history”, even though she lives in neighbouring Milan and has often visited Sesto to tell her story. She is even a member of ANED, like all other deportees, Jewish people and political opponents; people of all ideologies, beliefs and ethnic backgrounds. The mayor, instead, has made headlines for promoting initiatives of a different nature. Last January his council gave CasaPound (an Italian neo-fascist group) a hall in which to hold a convention. The opposition’s protests and a demonstration organised by the Antifascist Committee and National Association of Italian Partisans (ANPI, Associazione Nazionale Partigiani Italiani) weren’t able to stop the event from taking place. ANPI, however, was successful in blocking another far-right conference planned to take place in a hotel last November.

“I called the hotel’s director and said to him: ‘Do you know who they are?’ That was all it took,” Lina Calvi, president of ANPI Sesto, recounts. Wrapped in a purple scarf, her white hair tied in a bun, she smiles as she walks towards us in Villa Zorn’s garden. “We lost them,” she adds, pointing to an Art Nouveau-style dance floor and a restaurant where ANPI members held their meetings until 2017. “The new administration chose to rent them out to privates. We’re left with two rooms, but the clubhouse was the soul of our organisation and with the profits from the bar we were able to cover ordinary expenses”.

Lina reminisces about dance nights, exhibitions, debates. The nostalgia is palpable. “At the end of the war people wanted to dance; after all that suffering, they needed to have some fun. The dance hall was so important, people young and old would come to the clubhouse. Sesto used to be lively…”. One of her grandchildren calls her on the phone. Lina has always been a busy woman, balancing her private life and civic engagement. She even held the role of education councillor in the early 1990s. “Now they’ve even outsourced the two nursery services, which had always been the pride and joy of the town. Sesto was one of the first cities in Italy to invest in public support for working mothers”.

Lina lowers her gaze. She says she feels very close to Liliana Segre, denying the mayor’s claims that she has nothing to do with Sesto San Giovanni. “I remember when she told her story in our schools. The children would listen to her in solemn silence”.

In Piazza Rondò, a junction where commuters board the metro to Milan, former vice-mayor Felice Cagliani is waiting for us. His long political journey spanning various roles in left-wing administrations has led him to form a clear opinion: “The right, which has been governing the city for two years now, is trying to erase Sesto San Giovanni’s history, dismantling what the other parties have built over 70 years”. Sesto was one of the most important centres of the Resistance. It was known as the Italian Stalingrad due to the rooted presence of the Communist Party and large factories like Breda, Falck, Magneti Marelli, Pirelli, Campari. “But it was also a virtuous example of popular organising,” Cagliani stresses. “The evictions can be explained in this light: they want to draw a line under Sesto’s history, eliminating the associations that form the bedrock of the community’s cohesion by attacking the places that embody it”.

Historians agree that this town, with its 82,000 inhabitants, basically a suburb north-west of Milan, had a decisive role in 20th century Italy. The fact that the right won the last elections is probably due to multiple factors. Roberto Di Stefano launched his candidacy with aggressive populist propaganda, taking advantage of the general crisis of left-wing parties and growing disillusionment with politics on the part of the Italian public. On the local level, the new mayor came to power in the context of far-reaching transformations following the closure of almost all industrial production in the 1990s and the progressive disappearance of labour movements.

Due to its proximity to Milan and lower cost of living, over the last twenty years the proportion of foreign residents has grown to about 17 per cent. “On the left, we have our responsibilities to account for. The previous 70 years have left us ossified. We’re struggling to build an effective opposition and adapt to social changes. Though this doesn’t mean we haven’t tried,” Cagliani explains. He’s still on the frontline of forging a new identity for his city, starting with areas that are now in disrepair.

As a representative of Article One (an Italian social-democratic party), he was part of the delegation that went to the Health Ministry in support of a project called Città della salute e della ricerca‘ (“city of health and research”) last October. The plan would entail giving a new home to the Carlo Besta Neurological Institute and National Cancer Institute in an area formerly occupied by Falck, creating a public hub of excellence and injecting new life into an abandoned part of the Milanese hinterland. The idea developed by architect and senator for life Renzo Piano is based on the concept of ‘”non-consumption of land”. The new medical structure containing 650 hospital beds would be built on a more human scale, no higher than three stories and surrounded by a 55,000-square-metre green area containing 10,000 trees. At the moment, however, the council is more in favour of converting the area to private structures.

From an overpass in northern Sesto a muddy expanse of reclaimed land is visible. “It was supposed to be ready in 2020. But nothing has been done because of legal troubles with Lombardy’s regional administration going back to the time of Roberto Formigoni’s presidency (1995-2013, ed.), and financial issues with the construction firm,” says Cagliani.

“We’re fighting for this project, it would be a symbol of regeneration. It would ‘compensate’ the damage brought about by our industrial history. Until 1996, the year Falck ceased its activities, balconies in Sesto San Giovanni were normally covered with two centimetres of black dust. At the time, there wasn’t widespread environmental consciousness”. The match being disputed in Sesto is emblematic for the entire country. Its new identity could be built by drawing on both its past and a vision of long-term future renewal. It could be the first important Italian experiment in poly-centric development in the periphery of a large city.

Former deportee and architect Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso and his son Alberico decided to place the city’s Deportation Memorial on an artificial hill created using industrial waste.

The uphill path is covered in cobblestones, reminiscent of those in concentration camps. The steps evoke Mauthausen’s so-called “death staircase”, which prisoners were forced to climb while carrying granite boulders from the camp’s quarry: fatal falls occurred continuously – if space was needed for new prisoners, often the kapos would push people down the 186 steps to their deaths. A pillar at the top of the hill, which marks the starting point of a semicircle of stone plaques projected towards the horizon, represents a stylised human being, with large stones in the place of the head and feet. A minimalist representation of the absolute loss of freedom. Those same stones, Valota reminds us, “were the victims of an attack. And at the memorial organised by ANED and ANPI in October 2017, the mayor didn’t show his face nor did he send a gonfalon”.

Heading back to the centre, one can’t help but wonder whether, despite its considerable history, Sesto San Giovanni risks withering like so many municipalities in the Milanese hinterland. Those who grew up in these areas often call them “dormitories” for commuters. In the metropolitan area incorporating the Milanese province, a common fear is that Milan‘s revival as the economic capital of Italy, where new districts and services are flourishing, is happening at the expense of its environs, home to over 3 million people. The hinterland could simply become, as it already has in part, the huge new suburbs of Lombardy’s capital where, among other things, many local shops are closing their shutters permanently because they can’t compete with shopping centres. There are barely any places for people of any age group to meet. Green spaces, where children can play, are disappearing.

The ISEC foundation for contemporary history houses part of the ANED archive, including publications, photographs, even the secret committee’s sepia flyer exhorting workers to strike in 1944. Of the approximately 40,000 Italian deportees, 23,400 were political prisoners, about 10,000 were sent to camps in Italy and 8,000 Jews were sent across the Brenner Pass to camps in Austria and Germany. We’re reminded of this by Dario Venegoni, president of ANED, at the national headquarters in Milan, also known as the House of Memory (“Casa della memoria”). The writer and journalist, son of deportee survivors Carlo Venegoni and Ada Buffulini, explains: “We represent all deportees. We want to unite, not divide. Sesto’s story isn’t local or minor, but it reminds us that so many people were imprisoned in concentration camps because of their political work against fascism. And political initiative is needed to ensure the continued existence of an ANED chapter in Sesto”.

It’s evening by the time we’re back in Sesto. Valota is still at his computer. Most of his audio recordings have been transcribed and digitalised, but there’s still a lot of work to do for the archive: new research, recently discovered stories that need to be catalogued and documents that need to be reorganised. We’re joined by the young coordinator of the Sardines (a new grassroots political movement) for Sesto San Giovanni and Cinisello Balsamo, two towns with a combined population of 160,000. “I’m glad to meet you, Giuseppe, because ANED represents the political history that the populist right wants to erase. Antifascism and antiracism are the pillars of our network,” says Marcello Ierrera, a Politics student at Milan University.

“I grew up in a neighbourhood in Sesto that has a very high migrant population. They’re my friends, Italians like me. Discriminating against them makes no sense. In all my life, I’ve never known politics with a capital P. We young people are tired of political expression feeling like a talk-show debate, it shouldn’t be that who shouts the loudest or spreads the most fake news on social media comes out on top. Politics isn’t a branch of marketing”.

Valota replies, remembering those who gave their life for politics: “Sesto has always been broadly antifascist. The first great strikes date back to the so-called Two Red Years (‘Biennio Rosso’) between 1919 and 1921. In 1931, 1935 and 1939 three rulings of the fascist Special Tribunal for the Defence of the State sentenced 101 workers from Sesto San Giovanni. Another six were exiled. The working class was opposed to fascism because it allowed no freedom. There was economic suffering. All social and cultural life was planned, schooling was dictated by Rome, leaving no space for autonomy, and the concept of the citizen-soldier was inscribed in textbooks. In factories people suffered, they ate and spoke little”.

Things worsened considerably during the war. The alliance between Mussolini and Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler sent Italy into a conflict that it wasn’t prepared for, with atrocious consequences for its people. Valota continues: “Working hours increased and factories were militarised. Former soldiers, generals and colonels were brought in to enforce discipline alongside department heads. There were ration cards but the availability of rice and bread decreased as the war went on. Discontent was growing in the factories. Houses began to lose their heating, and it was cold at school and at work as well. People were getting visibly thinner while bombings left everyone terrified. In the end, hundreds of thousands of workers in the centre-north of the country decided they’d had enough”.

“It was a political strike in the highest sense of the term. As well as establishing economic demands, the clandestine flyers read: ‘Neither a man, nor a machine’. The Germans were thinking of moving production and machinery to Germany because strikes were unheard of in the country and, though few machines were shipped there, many men were”.

Hungarian philosopher Ágnes Heller, a survivor of both the Holocaust and Stalinist persecution, wrote that “active maintenance” is needed to keep democratic principles alive. Nothing can be taken for granted as fascism can return, including in different forms. Democracy, on its part, requires participation and constant collective commitment as its foundations have to be rebuilt each day. An expression of such dedication is embodied in Giuseppe’s care for his archive and Deportee House. However, the defence of human rights can’t be left solely to those who’ve experienced violations firsthand. This must be kept alive, passed on to young generations as an acquired heritage, so that the voices of those sent to their deaths aren’t silenced once again. The voices of those whose names are known and also of “those of whom no trace is left”, as the inscription chosen by Giuseppe Valota for the Deportation Memorial’s last plaque recites.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

As per tradition after 12 years India held Mahakumbh, the world’s largest spiritual congregation that has been attracting pilgrims from across the globe.

Workers in tea gardens of West Bengal, India, that produces Ctc tea for domestic consumption complain that they have been devoid of basic facilities while political parties make hollow promises during every elections which are never fulfilled.

India is in the middle of the elections, but sadly none of the politicians have uttered a word on man-animal conflict that has been devouring several lives every year.

Manipur, a state in north-east India, is still reeling under the tremors of violence that broke out last year devouring lives and paralyzing the economy.

The government of Tanzania is currently planning to evict more than 80.000 indigenous Maasai people from their ancenstral land

A new UNU-INWEH report on the global bottled water industry reveals the massive scale of this market and the lack of strict quality controls.

Isatou Ceesay founded a social enterprise that is helping to fight plastic pollution and empowering women and young people to gain economic independence.

In 2020, Mihela Hladin made a radical decision that many, in recent times, have probably considered. This is her story, with photos by Matt Audiffret.

The Brazilian government has started evicting illegal gold miners, responsible for the health emergency that has hit the Yanomami people.