Shell’s board of directors is being taken to court by ClientEarth for failing to move away from fossil fuels fast enough.

Much uncertainty remains in the transition period. Here’s what EU citizens living in the UK, and vice versa, should know about and expect from Brexit.

On the 31st of January 2020, the United Kingdom officially left the European Union. This started an 11-month period of discussions known as the transition period, which stands as possibly the most important period of negotiations in the country’s history. During it, rules on travel, trade and business as they currently stand continue to apply in the UK. At the end of it, however, the agreed upon terms will need to be implemented or, in what would be a worst case scenario for many, a “no-deal” Brexit will occur.

Coronavirus has brought further complications, with negotiations being delayed to deal with the pandemic, or moved online. While the latter may be an efficient alternative, it leaves little space for candour and flexibility. The EU had previously suggested extending the transition period, a proposal rejected by the UK. The offer has since been reiterated but a final decision must be made by June 2020 to give businesses enough time to respond. If an extension isn’t implemented, certain unresolved issues may increase the likelihood of a no-deal Brexit.

Many EU citizens living and working in the UK, as well as UK citizens in the EU, are now facing uncertainty with regards to their property, travel, jobs, businesses and trade. And the same is true for environmental legislation. Here’s a guide to what we know about the expected changes so far, in order to be better equipped to deal with a new Europe in 2021.

Although environmental legislation may not be the first area to come to mind when discussing the impacts of Brexit, the topic is of vital importance. For example, changes may affect the way UK waste is treated, vulnerable habitats are protected and biodiversity is allowed to flourish. Shortcomings on this front may be reflected in citizen’s wellbeing and livelihoods, so it’s vital for the UK to establish a strong environmental foundation to prevent negative outcomes.

Starting with the 1972 Environmental Action programme, the EU has continued to offer a forum for collaboration and coordination by shaping the policies of its member states. It has done so by introducing new legislation and statutory bodies enforcing these rules: in the UK alone, 80 per cent of environmental rules stem from the EU. The latter institution also provides funding for projects, which means that the EU Withdrawal Bill may heavily impact the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, which relies on European funding.

Although EU influence on UK environmental policy may have been viewed as a force for good, the relationship has not been without its problems. A number of shortcomings, such as overfishing in the UK’s waters due to the Common Fisheries Policy, have attracted strong criticism. This example shows that retaining what has been inherited from the EU may not necessarily always be the best approach for the UK. Its parliament may aim to improve on shortcomings and enforcement, as well as tailor its policies to individual circumstances.

“The UK has been a central driver for higher climate ambition in the EU,” according to Doctor Emma Emanuelsson Patterson, lecturer in the department of Chemical Engineering at the University of Bath, in England. She cites the fact that the radical environmental movement Extinction Rebellion is much stronger in the UK – a country that “exhibits very strong public pressure, which Brexit won’t change” – compared to her native Sweden.

However, there’s also reason to believe that the country may be lacking in its environmental resolve. In 2018, the government was taken to the court by the European Commission over its continued failure to meet nitrogen dioxide emission requirements. Although Environment Secretary Michael Gove has promised rigorous governance following Brexit, his newly proposed environmental watchdog will be unable to directly take the government to court. This already undermines the government’s accountability in failing to meet emissions targets. In addition, a recent conversation between the UK and US may lead to chlorinated chicken and hormone-pumped beef, among others, to be imported from the latter country. These goods would be illegal in the EU, and directly contrast the Conservative government’s manifesto of not compromising on “high environmental protection, animal welfare and food standards”. The final outcome is yet to be seen.

Brexit is expected to introduce a points-based system for obtaining working visas. Seventy points are needed and certain criteria must be met, among which is a minimum salary of 25,600 pounds (almost 32,000 US dollars) a year. Emanuelsson Patterson compares this to New Zealand, which “holds a visa category for skilled immigration”. However visas for jobs considered “low-skilled” won’t be readily available in the UK, even though they’re the foundation of its economy and are vital to general wellbeing and business growth. In fact, removing visas for them may increase the likelihood of illegal work and exploitation. “This may create a gap in the existing cheap labour workforce,” Emanuelsson Patterson points out, meaning that workers that can help look after the elderly, build homes and keep the economy strong overall will have to be sourced from elsewhere.

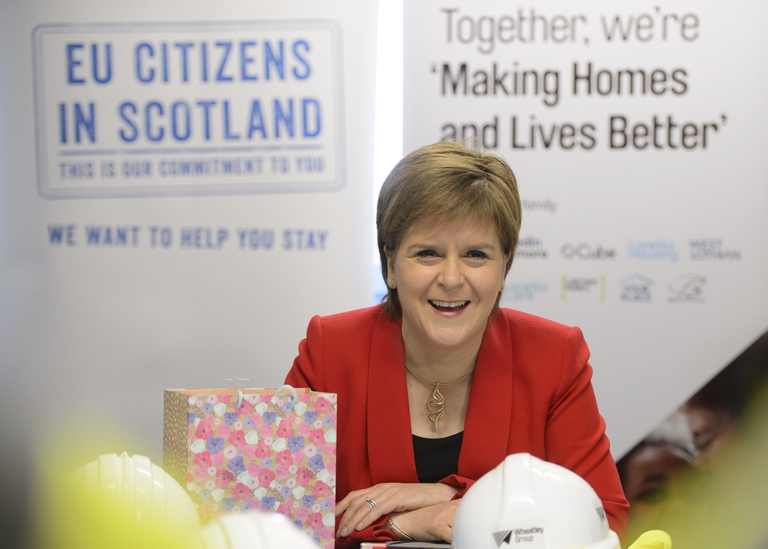

When it comes to living in the UK, EU, European Economic Area (EEA) and Swiss citizens will need to apply to the EU Settlement Scheme: with settled status, there’s no limit to how long one can stay in the country. Irish citizens don’t need to apply since a separate agreement exists. The settlement scheme is expected to provide access to public services and funds, and potentially British citizenship. A minimum of five years of living in the UK continuously entitles individuals to apply and, prior to this, a pre-settled status exists which has the same benefits but is only valid for five years.

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought about new complications, however. Some individuals may be in lockdown outside of the UK for more than six months in a twelve-month period, affecting the requirements for continuous residency, therefore jeopardising their eligibility. Others may be unable to access important documents or seek guidance from resolution centres, which may affect their ability to apply on time. Whether the government will take measures to mitigate these impacts is still uncertain.

Emanuelsson Patterson also points out that many British people who live in the UK work abroad, or vice versa. Double taxation agreements ensure that they don’t need to pay taxes twice but potential changes in this arrangement may cause some concern. However, the lecturer believes that “it’s in the interest of most countries to have a diverse workforce, and hopefully neither the UK nor the EU will want this to change”. When speaking of her personal experience of moving to the UK, she says she found a strong sense of community that welcomed her, and has positively integrated in British society. Overall, she doesn’t expect this atmosphere to change.

After the transition period, EU citizens will still be allowed to invest in UK property but this won’t automatically give them the right to live in the country.

Many EU buyers look on UK property as a good investment and around 9 per cent of it is owned by people born outside the country. The Association on International Property Professionals (AIPP) predicts an uncertain road for EU property investors at least for the next five or so years, especially due to short-term impacts on exchange rates. This may translate into rapid changes in exchanging the British Pound against the Euro, affecting businesses that depend on this. In addition, some large banks have stopped providing mortgages, therefore the AIPP advises EU citizens in the UK to buy a house outright.

Emanuelsson Patterson explains that she bought a house when she moved to the country: finding a mortgage was “more complicated and took longer” because of her husband’s New Zealand nationality, which meant that certain banks weren’t willing to provide mortgages. It was eventually possible to find a loan since mortgage provisions also “depend on banks’ internal regulations”. As of now, it’s unclear whether EU citizens may face these same challenges after the transition period. At the same time, “UK citizens have properties around the EU,” which means that the government may try to maintain positive conditions for EU citizens “to avoid more complications”.

It’s worth mentioning that the situation in Scotland is different, since there are no restrictions on foreigners buying residential properties.

The withdrawal agreement guarantees that British citizens who lawfully reside in an EU state will have the same rights as they have now: they’ll be able to continue living, working and travelling in the country. These conditions also apply to British citizens moving during the transition period, throughout which freedom of movement will remain in place. These same agreements refer to Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein (EEA countries) and Switzerland.

British citizens living in the EU will need to apply for residence status and have time until the 30th of June 2021 to do so. The automatic right to live and work in the EU will cease to exist after the transition period and British citizens will need to apply according to individual country’s existing immigration rules.

As of now, it’s still unclear whether British citizens in EU countries will be able to move freely to other countries in the Union. For now, the EU has added the UK to the list of visa-exempt nations, giving British citizens the right to travel for up to 90 days without a visa within a 180-day period. Whether this will change is yet to be seen.

The UN’s Universal Declaration on Human Rights and European Convention on Human Rights protect the legal rights of property owners within EU countries. However, Brexit may impact the ease with which UK citizens can buy properties in the EU in a number of ways.

Mortgages may become less available in foreign exchange markets, and property taxes for British (i.e. non-EU) citizens could be increased. This may reduce the likelihood of British investments in EU properties, which may also be exacerbated by the possibility of receiving fewer euros for pounds. British nationals will probably need a special visa allowing them to visit their properties more than a certain number of times each year, and the time allowed to stay in the country may be limited. Similarly, a special investment visa may become necessary for those wanting to buy a property: in some countries, this already exists for non-EU nationals.

It’s important to note that each country will determine its own conditions. In the case of Italy, for example, foreigners can buy properties as residents or non-residents: however, a visa is needed to stay in the property for more than three consecutive months. An additional working visa is then required for employment. It’s assumed that these conditions will also apply to UK citizens after the transition period.

According to a survey by the British Chambers of Commerce, one out of five businesses plan to move part or all of their operations out of the UK in the eventuality of a no-deal Brexit. 98 companies have already moved to the Netherlands, and more than 300 have contacted the chamber of commerce regarding a similar choice. This is because certain financial reliefs that UK businesses depend on may not apply in the future. There’s also the risk of reduced investor confidence due to aspects such as exchange rate volatility.

“The city of London represents around 10 per cent of the UK economy: if businesses move to new places this will reduce the monetary input in the national economy,” Emanuelsson Patterson points out. The global foreign exchange market has a daily global turnover of about 2.5 trillion pounds (over 3 trillion US dollars), with London accounting for 36.5 per cent of the total. This underlines the importance of the city in international markets, however it’s still unknown whether this status will change after the transition period.

When it comes to trade, for now the UK is still in a single market that allows a relatively free flow of trade with the EU. Following the transition period, EU goods will be monitored and traders will need to submit customs declarations, as well as be liable to goods checks, potentially causing delays. New tariffs that could affect the pricing and supply of goods may also be introduced. Businesses may need to apply for the Economic Operators Registration and Identification (EORI) that non-EU countries need, which may ultimately lead to a reduction in trade. At the moment, UK businesses are advised to switch to a UK-based supplier to avoid disruptions and issues within supply chains.

Although Brexit has brought great uncertainty, it’s worth noting that European governments seem to be invested in maintaining near status quo conditions. The final changes UK and EU citizens will experience are yet to be seen, but as Emanuelsson Patterson summarises, “it’s in the interest of all to retain a diverse workforce, maintain revenue streams and not jeopardise positive relationships”. It’s now hoped that favourable changes will come for all the stakeholders involved.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

Shell’s board of directors is being taken to court by ClientEarth for failing to move away from fossil fuels fast enough.

India’s GDP could fall by 90 per cent by 2100 if climate finance isn’t improved. As the country tackles Covid, it mustn’t lose sight of sustainability.

We must give back to nature more than we extract. The European Union’s circular economy plan sets the guidelines to embrace this paradigm shift.

While Africa’s Covid-19 response has been praised by some, the pandemic has triggered the continent’s first recession in 25 years.

We must decide: in a post-Covid world, will we put emphasis on sustainability to achieve a green recovery or dust ourselves off and continue as before?

Businesses should evaluate the risks and opportunities of climate change and its mitigation to ensure their long-term resilience and success.

At the dawn of a new era, women in Japan still face old challenges: they’re paid less than men and struggle to scale the professional ladder. How can the impasse be broken?

Inequality has increased anywhere in the world despite substantial geographical differences, with the richest 1% twice as wealthy as the poorest 50%. The results of the World Inequality Report 2018.

Mountain areas are home to around 1 billion people and provide goods and services. This is why the protection of healthy mountain ecosystems has become a must. The op-ed by FAO’s Mountain Partnership Secretariat.