The Louise Michel is the humanitarian rescue ship saving lives in the Mediterranean. Financed by the artist Banksy, it has found a safe port in Sicily.

Behrouz Boochani returned to being a free man during the course of this interview. The Kurdish writer was imprisoned by the Australian government in Papua New Guinea for six years.

His peaceful resistance has triumphed. After six years of imprisonment, trauma and torture, Kurdish writer Behrouz Boochani is free, the amazing news arrived whilst this interview was being carried out. The writer had been confined to one of the remotest places in the world, Papua New Guinea, where Australia detains thousands of asylum seekers. Boochani is currently in New Zealand and will depart for North America shortly. “They closed Manus prison two months ago in September and everyone was transferred to allocated apartments in Port Moresby, the Papuan capital. Most of us should be rescued by the end of November, but there are 46 people still detained and living in very hard conditions. We remain very concerned for them,” Boochani affirmed a few days prior to being released.

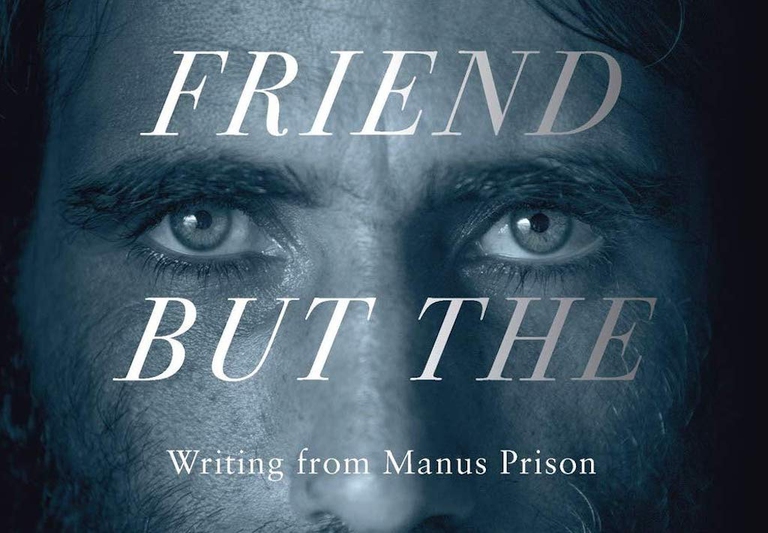

Boochani’s six years of struggles are captured in an internationally acclaimed book. No Friends But the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison, published in English in 2018, has reached all corners of the globe with truly unexpected force. The autobiographical account describes the suffering of refugees along the Asian route towards Australia. Boochani uncovers the accounts of people who, like him, had to hide in the Indonesian jungle before embarking on dangerous ocean voyages on boats managed by human traffickers, only to end up in prisons financed by Canberra. He evokes the desperation of his people, the persecuted Kurdish population of Iran. He remembers how he was forced to leave his country in 2013, as a 30-year-old journalist and director, due to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards’ irruption into the main office of “Werya”, the Kurdish magazine he founded. That day, 11 of his colleagues were arrested.

Thanks to his award-winning book, secretly sent to Sydney-based scholar Omid Tofighian who translated it into Farsi, Boochani has stripped the public of the possibility of justifying its indifference. For almost 20 years, the international community has been motionless with regards to what is happening off the Australian coast. Since 2001, the immigration model centred on rejection of migrants’ claims and their subsequent offshore detention has caused thousands of innocents to be deported, incarcerated, tortured as well as forced into hunger. Children, women and men who were forced to escape wars, abuse and misery from countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Somalia, Sudan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India and Nepal. These shameful camps – reminiscent of the ones where migrants are kept in Libya – are found on three Pacific islands: the Australian Christmas Island, Manus (part of Papua New Guinea) and Nauru, a small republic on the equator. Most camps have now been shut down following protests by Australian civil society and last year all children were transferred to the “mainland”. However, the fate of newly arrived “boat people” along with the 400 individuals trapped in Nauru and Port Moresby remains unclear.

Evidently, 18 years of reporting on prisoner suicides and peopling sewing their lips together as a form of protest weren’t a strong enough a cry for help. Nor was the fact that many children have suffered “resignation syndrome”, a condition which causes people to detach themselves from daily life and refuse to eat or drink. People needed something more. Like a modern Silvio Pellico (19th Century Italian author of the memoir “My Prisons”), Boochani has unleashed a virtuous domino effect.

His powerful 400-page long account overcomes distinctions in literary genres, leaves readers breathless while offering them an outstretched hand. In fact, the topic discussed concern us all: even the citizens of richer and freer countries are in need of help. The Kurdish intellectual tells us that “the way governments treat refugees and migrants is a kind of dictatorship. Democracies are broken if governments are allowed these terrible practices”. This interview was conducted over the course of a number of weeks via WhatsApp, the same platform that allowed Boochani to record and write his book with Tofighian’s collaboration. In the following answers, the author explains his point of view on what is currently happening to the Kurdish population in Syria and delineates his belief in nonviolent resistance. However, the author is clear about his goals for the future: “I will definitely write a variety of novels and create different artworks about different subjects. I don’t reduce myself only to this experience”. And no one should. Here below, the complete interview.

What do you think of the recent Turkish offensive against the Kurds in Syria?

What is happening in northern Syria isn’t only an attack on the Kurds but an attack on democracy and its values. The Kurdish people have established the most progressive democratic system in the history of the Middle East, a system based on equality. Now we’re faced with a fascist army who, together with terrorists groups, is attacking people who believe in democracy. I think the biggest threat to this world is state terrorism, especially the unwritten agreements between governments supporting each other in violating human rights. These days we see governments like the Turkish one hiding behind beautiful concepts like peace, humanity and morality. This is why Turkey named its genocide of Kurds “Peace Spring”, an absolutely ridiculous thing to do. Australia is doing exactly this: claiming that it’s saving people’s lives when really it’s torturing innocent people in remote prisons, hiding behind the shield of “morality”.

You were a child when your family tried to escape during the Iraq-Iran War (1980-88). What do you remember from this?

I was born in Ilam province, part of Kurdistan in western Iran. The war reached Ilam and I describe this in my book. The things I describe in my book aren’t necessarily about my family or people in Ilam. My account isn’t a memorial and many of the narrated events could be symbolic. I tried to write it as a way to represent many tragic stories that happened in that region: the Kurds were facing displacement and lost everything as a result. I tried to describe how war is horrible and how it destroys everything.

What does it mean for you to be Kurdish?

For me, being and living as a Kurd is the hardest thing in this world because you never stop witnessing people suffering. Superpowers and undemocratic governments are willing to take your identity away from you and deprive you of your human rights. Kurdish people have always struggled to maintain their identity. As an artist, I’m committed to taking part in this struggle, not only as a Kurd but as a human who deeply understands injustice and colonialism. This is why you can see Kurdish cultural elements in all my films and books.

Refugees in offshore locations are afflicted with “resignation syndrome” and suffer physical abuse and psychological trauma. At the moment, is there any medical assistance for the prisoners?

So far, eight people have died in Manus and five in Nauru, most of them because of medical neglect and others because of violence from the guards. All these deaths are proof of how this system uses sickness as a tool for torturing people. Also, we should be aware of people who are damaged physically and mentally: we’ve been living without medical treatment or medical facilities. Sick people are still struggling because of this. Fortunately, the Australian parliament passed the “Medevac bill” eight months ago, which helps a lot. According to this law, anyone who doesn’t receive medical treatment in PNG and Nauru should be transferred to Australia. Since this bill passed, 217 people have been moved and hopefully more will be transferred.

And how are you? How do you manage the pain that has built up over the last seven years of your life?

My body is damaged. Like other people, I’ve witnessed many terrible things here. I’ve seen friends die, people self-harm, attempt suicide and others being seperated from their families and children. I’ve seen so much humiliation and trauma. Of course, all of these images are with me and this harsh experience has become a part of me. It’s hard to carry all of this whilst keeping myself strong and positively minded. I’m not sure I can manage all this. I’ve struggled to stay alive and survive whilst also exposing this system. I don’t know if I have a true answer to this question.

What are the conditions of the refugees and how is your daily life?

They closed Manus prison two months ago and everyone was transferred to Port Moresby, PNG’s capital city. Two years ago we were more than 800 and now we’re just over 200. We’re in this city which isn’t safe enough, we don’t know what’s next. 46 out of 250 people are in jail here and living in very harsh conditions. We’re concerned about them because the government claims they’re not real refugees.

Italian right and far-right wing politicians like Matteo Salvini want to apply the “Australian migration model” in the Mediterranean. What would you say to them?

I would just like to say one thing. Don’t look at Australia as a model, don’t let your governments follow Australia. I don’t say this only because of refugees, I say this for your people and democracy. Australia has committed all of these crimes for years and its people have let the government do it, and now their society is facing a kind of dictatorship. Their democracy is broken because they let the government carry out a dictatorship in Manus. Now they’re treating people the way they treated refugees. Australia has lost its values.

Do you still believe in nonviolent resistance? What about in Kurdistan?

I’ve always believed in nonviolent resistance, even for Kurdistan. However, this doesn’t mean that when a fascist government like Turkey attacks your land and people, you don’t react. Kurdish resistance is always peaceful and Kurds have always struggled to create a democratic system in the Middle East. Our peaceful resistance in Manus made the Australian government feel shame and as a result everyone blames Australia and not us. We’ve challenged Australian laws in many ways and in fact we’ve educated them.

What are your hopes and goals for the future?

I’ve been writing and creating in Manus for years and now I’m going to share my work internationally. However, I will definitely write a variety of novels and create different artworks about different subjects. I don’t reduce myself only to this experience.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

The Louise Michel is the humanitarian rescue ship saving lives in the Mediterranean. Financed by the artist Banksy, it has found a safe port in Sicily.

Venezuelan refugees are vulnerable to the worsening outbreak in South America: while coronavirus doesn’t discriminate, it does affect some people more than others.

In the midst of India’s coronavirus lockdown, two dozen people lost their lives in a desperate bid to return home: migrant labourers forced to leave the cities where they worked once starvation began knocking at their doors.

The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration was signed by 164 nations in Marrakech. This is what the non-binding agreement that encourages international cooperation stipulates.

The winners of the World Press Photo 2019 tell the stories of migrants in the Americas. From the iconic image of a girl crying on the border between Mexico and the United States to the thousands of people walking from Honduras towards a better life.

The Semìno project is a journey of discovery through different countries’ food habits, offering migrants employment opportunities and allowing us to enjoy the properties of vegetables from all over the world.

Travelling across the new route used by migrants to cross the Balkans and reach Trieste in Italy, a reportage that documents the social, economic and political changes of the countries along the way.

The countries hosting the most refugees aren’t the wealthy, Western ones. An overview by NGO Action Against Hunger reminds us that refugees and internally displaced people are far from being safe.

The solar plant in Jordan’s Azraq refugee camp has started to produce energy, allowing Syrian refugees in the camp to have electricity in their tents. It’s the world’s first refugee camp to be powered by renewable energy: a 2MW plant managed by the UNHCR and financed thanks to the Brighter Lives for Refugees campaign launched