Three people putting the protection of the planet before themselves. Three powerful stories from Latin America, the deadliest region for environmental activists.

Dal guardiacaccia che protegge i gorilla nel Parco dei Virunga, al piccolo agricoltore che lotta contro una miniera. Ecco chi sono i sei eroi dell’ambiente del 2017.

For some, environmental protection is a job. For others, it’s a need or a vocation, like a fire that burns inside that makes them put their life on the line to protect nature. Since 1990, the Goldman Environmental Prize honours environmental activists in six continents. The six winners of the 2017 Goldman Environmental Prize have been awarded in San Francisco, California, on 24 April.

This year’s ceremony was dedicated to Isidro Baldenegro López, an activist of the Native American Tarahumara, Mexico, and Goldman Environmental Prize recipient in 2005. He was murdered on 15 January because of his non-violent fight to protect ancient forests from deforestation. He went through the same fate of Berta Cáceres, Honduran activist who fought to protect her communities’ rights and lands. She was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2015 and was murdered in 2016. In many countries, environmental protection has a high cost. But Berta’s and Isidro’s efforts haven’t gone wasted, as many other activists inherited their battles, hopes and dreams.

The Goldman Environmental Prize, now in its 28th edition, awards six people from all over the world every year. This year’s winners are Uroš Macerl (Slovenia), Prafulla Samantara (India), Mark Lopez (United States), Rodrigo Tot (Guatemala), Rodrigue Mugaruka Katembo (Congo), and Wendy Bowman (Australia).

Uroš Macerl, 48, is an organic farmer and chairman of the environment organisation Eco Krog. His family farm in the Trbovlje region, central Slovenia, is located near a cement factory owned by Lafarge Cement powered with petroleum coke, a byproduct of oil refining. The cases of cancer in the area are significantly higher than in the rest of the country due to the factory’s toxic emissions. Many farmers witnessed heavy losses as pollution contaminated air, soil and water. Macerl had to stop cultivating his fields due to air pollution, but he has since been raising sheep instead. In 2009 Lafarge Cement obtained the authorisation to burn hazardous industrial waste, claiming that the emissions would have a negative impact only areas within 500 metres of the factory. Macerl’s farm is in that area, so he tried to contest the authorisation. Even if the government initially ignored him, he won a lawsuit, but the court’s sentence went unapplied. The European Court of Justice intervened, calling on Slovenia to take on its responsibility to comply with communitarian regulations on pollution. So, Slovenia’s government ordered the shutdown of the cement factory in 2015. Macerl won his battle.

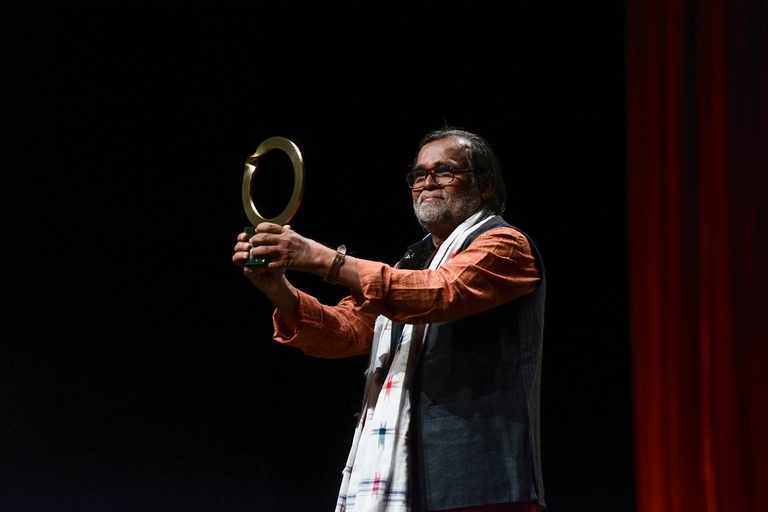

Prafulla Samantara, 65, was raised in a family of Indian farmers and has the heavenly aspect of a knowledgeable leader. He led a 10-year legal battle to protect the rights of the indigenous tribe of Dongria Kondh and to protect the Niyamgiri Hills in the state of Odisha, eastern India. This area is sacred to natives and is home to an incredible biodiversity, from the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) to the Indian elephant (Elephas maximus indicus). In this area, a bauxite mine was set to be built by the Odisha State Mining Company. The mine would have destroyed 1,660 acres of pristine forest, polluting water sources critical to millions of people. Also, many roads to carry bauxite would have been built, making forests vulnerable to illegal loggers and poachers. In 2003 Samantara decided to represent local communities in court – as they don’t speak English and lack access to the Internet – to protect the sacred hills, and started to organise demonstrations to block works. After a long legal battle, Samantara won his battle. The mine won’t be built and local communities obtained veto power on mining projects in their lands.

Mark Lopez, 31, grew up in a family of activists committed to protecting the rights of Hispanic communities in East Los Angeles. Lopez persuaded the state of California to provide comprehensive lead testing of the area, polluted by a battery smelter for over three decades. Exide took over the smelter in 2000 and ramped up the volume of batteries processed at the plant—and with it, emission levels of dangerous pollutants such as lead and arsenic. A sampling of dust on rooftops of nearby buildings found lead levels of 52,000 parts per million—where 1,000 parts per million is considered hazardous waste. Lead accumulates in the body over time and can cause learning disabilities even at very low levels, and as such, there is no safe lead level in children. In March 2015, after coming under investigation, Exide agreed to shut down the plant but left little means to clean up the contamination beyond the smelter site. Mark Lopez, with the support of his organisation Yard Communities for Environmental Justice (EYCEJ), got the governor of California to approve 176.6 million dollars for the testing and cleanup of affected homes.

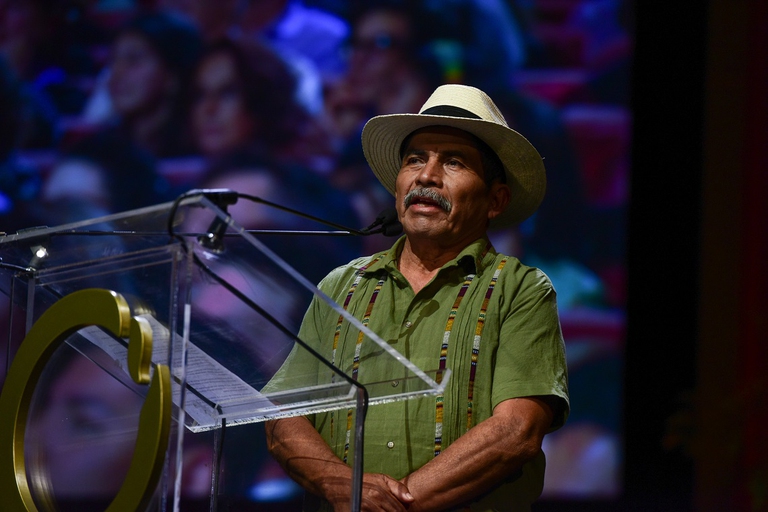

Rodrigo Tot, 59, is a Guatemalan indigenous leader who led his community’s peace revolution against the construction of a nickel mine in El Estor region, on the shores of Lake Izabal. This area is crucial to the Q’eqchi people that depends on fishery and agriculture for its livelihood. Due to waste water from mining, the lake became the most polluted in the country. The price of nickel gradually dropped and the situation returned to normal levels. The global price of nickel rebounded, and in 2006, the mining companies returned to El Estor. The company’s security forces began to forcibly remove people from their land, in violation of international treaties that require free, prior, and informed consent of indigenous communities. In 2011 the Constitutional Court issued a landmark decision recognizing the Q’eqchi’s collective property rights. However, the government has yet to enforce the court’s ruling, and the mining company continued to pursue the expansion.

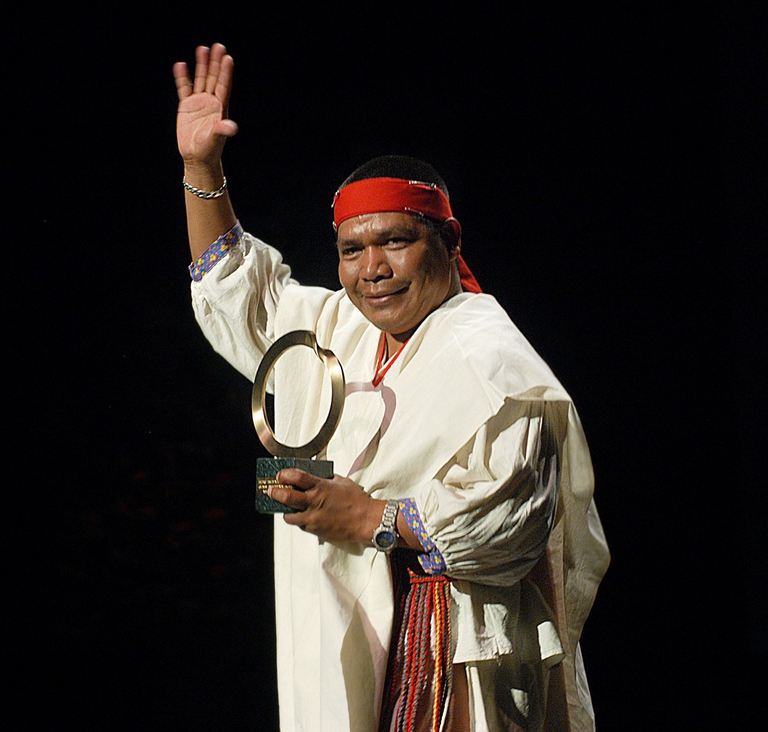

Rodrigue Mugaruka Katembo, 41, is a Congolese park ranger in Virunga, one of the planet’s richest and most fragile ecosystems home to the last mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei), which are threatened by poaching, the civil war and oil drilling. Katembo redeemed himself from his past as child soldier becoming the main character of Virunga, a documentary nominated for the Academy Awards in 2015 as best documentary. Katembo went undercover to document and release information about bribery and corruption in the quest to drill for oil in Virunga National Park, resulting in public outrage that forced the company, SOCO International, to withdraw from the project. Katembo has paid an enormous price for his activism. In September 2013, just days after he had stopped a SOCO team from building a telecommunications antenna inside the park, Katembo was arrested and tortured for 17 days. However, thanks to his commitment and the documentary’s success, SOCO stopped exploiting the area.

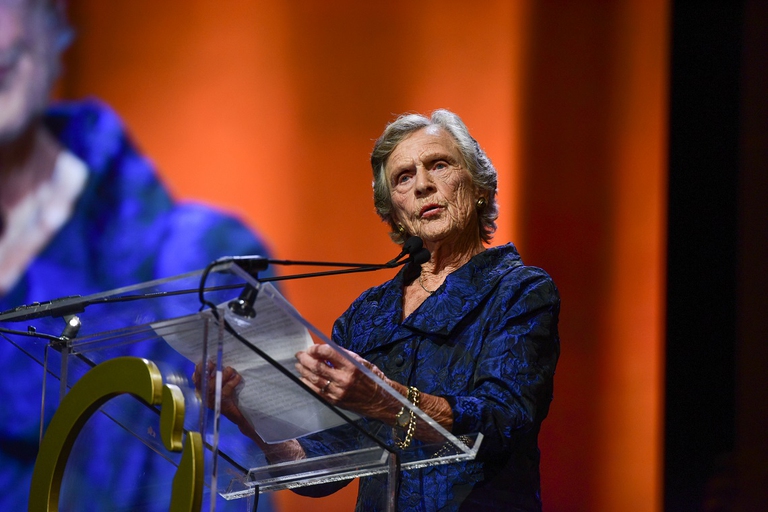

Is an octogenarian able to stop the apparently all-powerful mining industry in Australia? Wendy Bowman, 83, did it. Thanks to her detemination, she convinced the community of New South Wales (NSW), on Australia’s eastern coast, to refuse multinationals’ offers for lands to expand the Ashton mine. The Land and Environment Court issued a historic ruling: The Ashton expansion could proceed, but only if Yancoal could get Bowman to sell them her land. It was the first time an Australian court placed this kind of restriction on a mining company. Bowman refused offers of millions from Yancoal, and is now working on a plan to have Rosedale protected in perpetuity. She continues to be an advocate for the community’s health and environment.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

Three people putting the protection of the planet before themselves. Three powerful stories from Latin America, the deadliest region for environmental activists.

The Amazon became an alternative classroom during the pandemic. Now, the educational forest in Batraja, Bolivia, lives on to teach children and adults the value of nature.

Influential scientist, activist and author Vandana Shiva fights to protect biological and cultural diversity, and against GMOs.

Kimiko Hirata has blocked 13 new coal plants in Japan, but she hasn’t done it alone. The 2021 Goldman Prize winner tells us about her movement.

The Goldman Environmental Prize, the “green Nobel Prize”, is awarded annually to extraordinary activists fighting for the well-being of the planet.

We talk to Shaama Sandooyea, activist and marine biologist from Mauritius onboard Greenpeace’s Arctic Sunrise ship in the heart of the Indian Ocean.

Our species took its first steps in a world covered in trees. Today, forests offer us sustenance, shelter, and clean the air that we breathe.

Arrested for supporting farmers. The alarming detention of Disha Ravi, a 22-year-old Indian activist at the fore of the Fridays for Future movement.

Water defender Eugene Simonov’s mission is to protect rivers and their biodiversity along the borders of Russia, China and Mongolia.