The oil giant TotalEnergies must defend itself against accusations of failing to take into account the climate consequences resulting from the use of its products.

AXA, one of the world’s biggest financial services companies, is dumping investments in tar sands and ending insurance for controversial oil pipelines, taking fossil fuel divestment to new heights.

After announcing that it would divest from coal, French insurance giant AXA divests from tar sands, announced that it will cease insuring the sector and will divest over 3 billion euros (3.5 billion dollars) from tar sands, coal companies and three major pipeline projects. The announcement was made by AXA CEO Thomas Buberl in a speech at the One Planet climate summit convened by French President Emmanuel Macron. It also raised its goal for investments in green energy and buildings from 3 billion to 12 billion euros by 2020. The coal divestment criteria are: power companies which generate over 30 per cent of their electricity from coal; companies with plans for new coal power plants totalling over 3,000 megawatts; and mining companies with either a coal share of revenues over 30 per cent, or with an annual coal production higher than 20 million tons.

AXA is the world’s third largest insurance company in terms of assets and the second largest financial services company in terms of revenue. It was one of the first major financial companies to start selling off coal investments in 2015, with a 500 million euro divestment and earlier this year, AXA Investment managers pledged to divest 165 million euros (175 million dollars) of its fixed-income portfolios and 12 million euros (13 million dollars) of equities portfolios as a result of its new coal policy.

“It is particularly encouraging to see investors acknowledging that support for the Paris Climate Agreement means kicking companies out of their portfolios if those companies continue planning new fossil fuel projects which would destroy our chances of meeting the Paris goals.”

(Patrick McCully, Climate and Energy Programme Director, Rainforest Action Network)

Tar sands oil is one of the dirtiest fuels on the planet. Producing oil from the tar sands is like scraping the bottom of the oil barrel. Tar sands consist of a mixture of 85 per cent sand, clay and silt; 5 per cent water; and 10 percent crude bitumen, the tar-like substance that can be converted to oil. Bitumen doesn’t flow like crude oil, and getting it out of the tar sands is a messy job. The current technology, which has evolved relatively little since it was first developed in the early 20th century, is a hot-water-based separation process that requires huge quantities of water and energy.

Over 80 per cent of the established tar sands reserves are very deep and must be extracted on site by injecting high-pressure steam into the ground to soften the bitumen so it can be pumped to the surface. Once separated from the sand, the bitumen is still a low-grade, heavy fossil fuel that must undergo an energy-intensive process to upgrade it into a synthetic crude oil more like conventional crude, either by adding hydrogen or removing carbon. There are numerous deposits of oil sands in the world, but the biggest and most important are in Alberta, Canada and Venezuela, with lesser deposits in Kazakhstan and Russia.

The environmental consequences of oil production from tar sands are major, beginning with its effects on climate change. While the end products from conventional oil and tar sands are the same (mostly transportation fuels), producing a barrel of synthetic crude oil from the tar sands releases up to three times more greenhouse gas pollution than conventional oil. This is a result of the huge amount of energy (primarily from burning natural gas) required to generate the heat needed to extract bitumen from the tar sands and upgrade it into synthetic crude. The energy equivalent of one barrel of oil is required to produce just three barrels of oil from the tar sands.

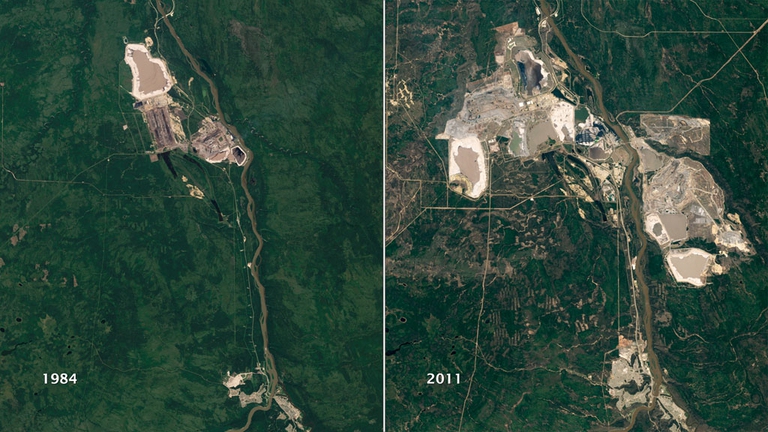

The environmental consequences of tar sands development hardly stop with climate change as it affects forests, water and wildlife. Tar sands are found beneath boreal forest, a complex ecosystem that comprises a unique mosaic of forest, wetlands and lakes. Canada’s boreal forest is globally significant, representing one-quarter of the world’s remaining intact forests. Beyond the ecosystem services it provides, it is home to a wide variety of wildlife, including bears, wolves, lynx, and some of the largest populations of woodland caribou left in the world. Its wetlands and lakes provide critical habitat for 30 per cent of North America’s songbirds and 40 per cent of its waterfowl.

If currently planned tar sands development projects unfold as expected, approximately 3,000 square kilometres of boreal forest could be cleared, drained and strip-mined to access tar sands deposits close to the surface. Studies suggest that this scale of industrial development could push the boreal ecosystem over its ecological tipping point, leading to irreversible ecological damage and loss of biodiversity. According to Environment Canada (the Canadian equivalent of the United States Environmental Protection Agency), development of the tar sands presents “staggering challenges for forest conservation and reclamation.”

Water withdrawals for tar sands surface mining operations also pose threats to the sustainability of fish populations in the Athabasca River. Tar sands mining operations withdraw 2-4.5 barrels of fresh water from the river for every barrel of oil they produce. Current operations are permitted to withdraw more than 349 million cubic metres of water per year, a volume equivalent to the amount required by a city of 2 million people. But unlike city effluent waters, which are treated and released back into the river, tar sands mining effluent becomes so contaminated that it must be impounded and end up in “tailings ponds”.

#OnePlanetSummit “Why are we stepping up the fight against #climatechange” Read the op-ed by @thomasbuberl, #AXA CEO: https://t.co/G9ItOOIL0O

— AXA (@AXA) 14 dicembre 2017

This isn’t the first major blow to tar sands companies in just the past two months. The French bank BNP Paribas and ING in the Netherlands have both recently divested from tar sands. French corporate and investment bam Natixis also sent out a communiqué stating that it will no longer finance “oil extracted from tar sands or companies whose business primarily relies on exploiting oil extracted from tar sands.” Earlier this month, bank Société Générale, also French, made a similar announcement, while Credit Agricole said it will exclude from its portfolio “the worst-performing and most dangerous hydrocarbons,” meaning all extra heavy oil projects “in particular, all oil sands projects”. Norway’s largest life insurer, KLP also announced that it would exclude from its portfolio any firms that derive 30 per cent or more of revenues from the extraction of tar sands and in the same week the World Bank announced it would cease financing upstream oil and gas after 2019.

A plus 4 degrees Celsiu world isn’t insurable. As a global insurer and investor, we know that we have a key role to play. We have made some pioneering moves since 2015, notably by starting to divest from coal, setting an ambitious green investments target and restricting our insurance business with the coal industry. We’re proud to have taken these decisions and to have inspired other actors. Today, in the spirit of the Paris Agreement, we want to accelerate our commitment and confirm our leadership in the fight against global warming.

(Mark Pearson, Chief Executive Officer of AXA)

Some of the biggest investor firms are beginnning to see the larger picture and understanding the advantages of pulling out of “un-investable” and “uninsurable” businesses like tar sands. If governments have to fulfll their commitments to reach the Paris Agreement many coal, oil and gas reserves could become worthless and the risk of stranded assets, those that become obsolete, would become a glaring reality for all. As such, 2018 promises to be a year that will see a massive movement in the tide against financing fossil fuels.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

The oil giant TotalEnergies must defend itself against accusations of failing to take into account the climate consequences resulting from the use of its products.

AXA Investment Managers, a France-based investment service provider, has pledged to divest 165 million euros (175 million dollars) of its fixed-income portfolios and 12 million euros (13 million euros) of equities portfolios as a result of its new coal policy. It announced that it won’t invest in companies that derive more than 50 per cent of their

The American billionaire and his co-founders of the Breakthrough Energy Coalition launched a new investment fund for developing clean energy technologies and tackling climate change.

The climate impact of the U.S. Gulf of Mexico’s oil and gas production could be higher than government inventories indicate.

ReconAfrica hunt for oil and gas threatens vital waterways home to the world’s largest elephant population and endangered wildlife

Niseko, Toya-Usu and Shiraoi are three Hokkaido destinations for travellers who want to feel close to the communities they’re visiting.

Despite environmental warnings, the Tanzanian government is set to build a dam in the heart of the Selous Game Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Researchers from the IFM at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia have tested a novel method for removing silicon from used solar panels.

The Congolese government is allowing energy firms to bid for access to its vast oil and gas reserves, risking terrible ecological and climate effects.