Three people putting the protection of the planet before themselves. Three powerful stories from Latin America, the deadliest region for environmental activists.

Time magazine’s 100 Women of the Year project sheds light on influential women’s stories, from Amelia Earhart to Greta Thunberg. A selection of some of the greats for International Women’s Day.

Every year, for 72 years, Time magazine named a Man of the Year: a prime minister, a powerful industry executive, a president. When in 1999, in an attempt to highlight gender equality, the nomination to Man of the Year was changed into Person of the Year, it was still often men who made the front cover. Many women who changed history never even got the chance to be nominated.

This is why the US-based magazine created the 100 Women of the Year project: 100 women, 10 for each decade, from the 1920s up to today. One hundred covers for one hundred women whose stories of intelligence, talent, genius and strength, but also of grace and elegance, have remained in the shadows for too long. And for too long, society – locked in stereotypes and systemic inequality – has failed to recognise their achievements. It’s time to cast a new light on history.

In 1953, an image was shown to James Watson, a molecular biologist who, at the time, was studying the structure of DNA. It was no ordinary image; it hid a scientific discovery of extraordinary magnitude that Watson immediately recognised. A black cross of reflections showed, for the first time in history, DNA emerging from a helical structure. The image was an X-ray photograph created by chemist Rosalind Franklin, who was able to provide the first stepping-stone to the scientific discovery of the double helix structure of DNA molecules. Watson and his colleagues Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins legitimately came into possession of the image and data, and no one ever reported it as intellectual theft. In 1953 they published their findings and in 1958, at the age of 37, Franklin died of cancer. In 1962 Watson, Crick and Wilkins won the Nobel Prize. Everyone forgot about Rosalind Franklin.

“Pata pata pata” plays on the radio and echoes in homes all over the world. It’s 1967 and the worldwide hit by Zenzile Miriam Makeba, South African artist from Johannesburg, becomes the soundtrack to the opening act of the revolution against apartheid. In 1960, Makeba was forced into exile to the United States. For another 34 years, apartheid in South Africa wouldn’t come to an end, but Mama Africa’s music, as she’s often called, wasn’t a hymn to fight the regime; it was art, freedom and, more simply, a testimony of the reality of those years. “People think I consciously decided to tell the world what was happening in South Africa,” Makeba once said during an interview. “No! I was singing about my life, and in South Africa we always sang about what was happening to us – especially the things that hurt us.”

Makeba returned to her country in the early 1990s, when the apartheid regime was becoming weaker and her music returned to being played freely, healing the soul of a wounded nation.

In those same years, another revolution was taking place in the US. In 1962, Silent Spring was published, a powerful book denouncing the use of pesticides and other chemicals such as DDT, the so-called “elixirs of death”. Written by biologist Rachel Carson, it changed America. The book was so powerful that it was strongly opposed by the chemical industries who feared their economic and political interests would be threatened.

Carson accused these companies of spreading misinformation, and public officials and politicians of doing nothing to limit the misleading marketing strategies promoted by them. Since the late 1950s, even before the book was published, Carson had focused her attention on environmental conservation, particularly on the ecological consequences of pesticide use. The publishing of Silent Spring was delayed for a while because Carson was forced to have a mastectomy due to breast cancer in 1960. The biologist was among the first people to understand the extent and impact of human activities on the environment and the planet.

The book led to a national ban on DDT for agricultural use and helped inspire an environmental movement that led to the creation of the US Environmental Protection Agency, which still resists today, notwithstanding Trump’s unbridled anti-environmentalism.

Rachel Carson, author of “Silent Spring,” set in motion a movement that produced Earth Day, the Environmental Protection Agency and a transformation in how Americans see the world they inhabit #womenoftheyear https://t.co/JhbLOoWrNX

— TIME (@TIME) March 6, 2020

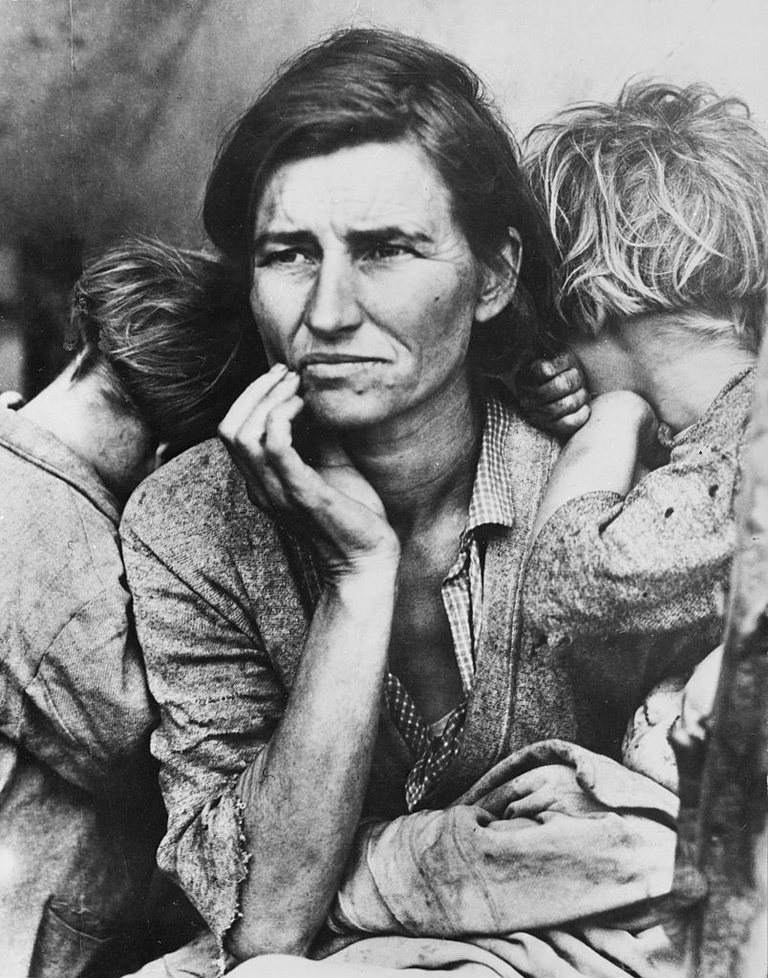

From a book, to a photo that changed America. It depicts a 32-year-old mother, Florence Owens Thompson, and her three children. It was taken by Dorothea Lange who, in 1936, was finally on her way home after a month of work in California’s farmer camps. Lange, however, felt she hadn’t completed her project so she turned her car around and went back. The photo, entitled Migrant Mother, became the symbol of the Great Depression, it travelled around the globe and is now considered one of the most famous photographs ever taken. An indelible trace that tells the story of hunger and poverty during those years.

“She said that they’d been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food,” said Lange of the migrant mother. “There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it”. When Lange returned home, she told the editor of a San Francisco newspaper about the conditions in the camp and gave him two of her photographs. The director informed the federal authorities and published an article that included them. In response, the government sent help to prevent people from starving to death. Through her lens, Lange was able to capture people’s dignity, even in times of suffering. Her work inspired a wave of social change, even though many of her photographs were suppressed until after the war.

It’s 1983 and Parisian-born Françoise Barré-Sinoussi extracts the HIV virus from the swollen lymph nodes of AIDS patients, together with Luc Montaigner. Barré-Sinoussi hadn’t intended to become a scientist but after obtaining a doctoral degree at the Faculty of Science in Paris, she began doing research. On the 6th of October 2008, she was awarded a shared Nobel Prize for Medicine with Luc Montaigner for discovering HIV and developing drugs that changed the lives of millions of people. Almost 40 years after her discovery, 38 million people around the world still live with HIV. Barré-Sinoussi knows her work isn’t finished yet.

“Yes, we can,” cried Obama’s supporters during his electoral campaign, a chant of strength and unity, embraced by social movements wanting to bring America closer to liberal democracy. And yet, “yes, we can” has a much longer life than the former president’s campaign: it began in the 1970s in another language. “Sí, se puede” was Dolores Huerta’s anthem. Huerta, a worker’s rights activist, was born in New Mexico in 1930 from a farmer unionist father and a mother who used to welcome farm workers in her hotel at reduced rates.

At the age of 32, Huerta, together with Cesar Chavez, founded the National Farm Workers Association and in 1965 led a farmers’ strike in California that turned into a national boycott and led to better pay, benefits and protection for thousands of workers. At a time when less than 40 per cent of women were in the workforce, Huerta gave them as well as trade unionists a voice, creating a movement for economic justice and dignity for all and inspiring young activists across the country.

Sitting in her aeroplane, aviator Amelia Earhart defied all social conventions regarding women’s place being in the home. A woman’s place is where she chooses to be, and for Earhart, that place was the sky. In 1932, she was the first woman to fly over the Atlantic Ocean, from Newfoundland in Canada to Ireland, and on the 11th of January 1935 she became the first woman to accomplish the feat of flying from coast to coast of the American continent, from Mexico City to New York City. She also flew from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, California, establishing herself as the first person ever to fly over both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

When (women and men) fail, their failure must be a challenge to others.Amelia Earheart

She always chose to go all the way, despite an open letter urging her to not fly in the days leading up to her journey from Hawaii. In it, she was reminded that ten people had died attempting the 3,800 kilometre-long crossing. Earhart’s ultimate aspiration, to become the first person to circumnavigate the Earth around the equator, led to her disappearance on the 2nd of July 1937.

For much of her life, Frida Kahlo remained in the shadow of her successful husband, Mexican artist Diego Rivera. In 1938, a press release for her first solo exhibition described her as “Diego Rivera’s wife” before admitting that the artist “proves herself a significant and intriguing painter in her own right”. The exhibition was only the beginning for Kahlo whose art – breathtaking paintings and surreal self-portraits – reached the whole world.

In her paintings, she represented taboo issues such as abortion or breastfeeding and emphasised her unibrow and moustache in strict defiance of gender stereotypes. A strong symbol of Mexican folklore identity, Kahlo also incorporated traits of indigenous art in her works, which explode with colour, expressing suffering as well as lasting joy and resilient temperament.

In 1938, she exhibited a painting in Paris, becoming the first Mexican artist of the 20th century to have her work purchased by the Louvre, even before her husband Rivera. Kahlo had many health problems; the body’s suffering, like that of the soul, is an ever-present theme in her iconography. She contracted polio as a child and at the age of 18 fell victim of a terrible bus accident that left her debilitated and forced her to have many surgeries for the rest of her life. She was forced to have several abortions and her relationship with Rivera was plagued by his constant infidelity.

It was difficult to decide whose story to tell amongst Time’s 100 women, but one thing was clear from the start: this woman had to be chosen. Simone de Beauvoir revolutionised feminist thinking. In 1949 she published The Second Sex: “It was a revelation. De Beauvoir exposed a long-hidden truth: that there is no female nature. She consulted biology, history, mythology, literature, ethnology, medicine and psychoanalysis to question the roles assigned to women. The book told me that I control my destiny. If there’s no fixed female essence, then we too are only what we do. The Second Sex provided me with weapons to understand, to defend, to respond and to persuade. It gave me the desire to write, an exercise in reclaiming the self,” Leïla Slimani writes in Time magazine.

In 1954, De Beauvoir won the highest French literary prize for her novel The Mandarins and in 1971 she wrote the text of the Manifesto of 343, a French petition to legalise abortion. She and Jean-Paul Sartre met in 1929 and were together for life, although they never lived according to the canons of traditional couples. De Beauvoir was a free woman and her thought reflected an essence of liberty.

The liberation of women will only happen with the change of society as a whole and, consequently, with the change of men as well.Simone de Beauvoir

In addition to the already-published 11 covers of women nominated as Person of the Year, Time created 89 new covers, many of which the work of talented artists. The most recent cover, in 2019, portrays Swedish activist Greta Thunberg. Thunberg, with her strikes, started a global movement at the young age of 15, dominating the headlines for months and succeeding in a seemingly impossible mission: bringing the world’s attention, including that of the media, to the fight against climate change.

Read more: News and stories about Greta Thunberg

In 2019, Thunberg became the youngest Time Person of the Year in history. The cover of the Swedish girl reflects what her perseverance has shown: that she’s part of a generation of young leaders ready to come forward where many others have faltered thus far. What started in August 2018 on the steps of Stockholm’s parliament with a lonely teenager, her hoodie and a sign saying “school climate strike” became a global protest in 150 countries, with some 7 million people joining the strikes in September last year for the largest climate rally in human history.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

Three people putting the protection of the planet before themselves. Three powerful stories from Latin America, the deadliest region for environmental activists.

Influential scientist, activist and author Vandana Shiva fights to protect biological and cultural diversity, and against GMOs.

Kimiko Hirata has blocked 13 new coal plants in Japan, but she hasn’t done it alone. The 2021 Goldman Prize winner tells us about her movement.

The Goldman Environmental Prize, the “green Nobel Prize”, is awarded annually to extraordinary activists fighting for the well-being of the planet.

One in three women have suffered physical or sexual violence. With contributions from Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America, we look at how this shadow pandemic affects every corner of the world.

The Istanbul Convention against gender-based and domestic violence marks its tenth anniversary. We look at what it is, who its signatories are, and what the future might hold.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen reminded us of the gravity of violence against women around the world, and of the Istanbul Convention’s utmost importance.

We talk to Shaama Sandooyea, activist and marine biologist from Mauritius onboard Greenpeace’s Arctic Sunrise ship in the heart of the Indian Ocean.

President Erdoğan has pulled Turkey out of the Istanbul Convention, key in the fight against gender violence, claiming that it favours the LGBT community rather than family values.