Nearly 100 people have died in the heatwave in India that has badly hit millions of people who work under the blazing sun to earn their livelihood.

American marine biologist James Estes has recently unveiled that sea otters, marine mammals native to the coasts of the North Pacific Ocean, contribute to saving our planet. His research, recently published in the book Serendipity: An Ecologist’s Quest to Understand Nature, observes wildlife behaviour through the interactions of predators with prey populations. Such synergies, called trophic

American marine biologist James Estes has recently unveiled that sea otters, marine mammals native to the coasts of the North Pacific Ocean, contribute to saving our planet.

His research, recently published in the book Serendipity: An Ecologist’s Quest to Understand Nature, observes wildlife behaviour through the interactions of predators with prey populations. Such synergies, called trophic cascades, helped Estes reveal the importance of predators in preserving healthy ecological ecosystems.

Estes spent most of his career in the Aleutian Islands, located in the North Pacific Ocean and stretching from Alaska to Russia. Thanks to their remoteness, these lands remained unspoilt until two hundred years ago, though this changed with the arrival of fur trappers.

Sea otters, at the time thriving in numbers across the islands, were hunted for their thick and dense pelt and became close to extinction by the turn of the 20th century. This fate was overturned by an international ban, which saved the mammal from eradication and recovered its populations, although unevenly, across the archipelago.

Always interested in food-chains, Estes was intrigued by the impact that the near extinction of sea otters might have had on local ecosystems. He began comparing coastal areas where sea otters had survived with those where they had disappeared, and found that their ecological benefits go far beyond local ones.

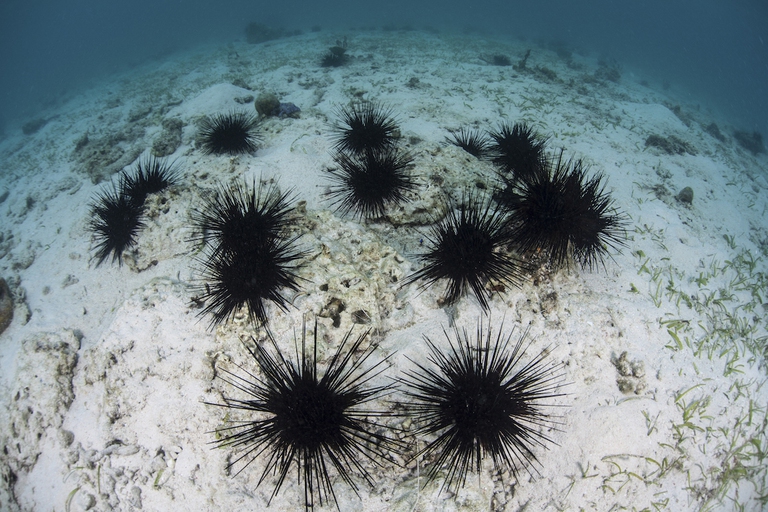

Sea otters feed on sea urchins, crabs and other shellfish, cracking them open with stones before eating them. To survive, an adult sea otter needs to eat up to 38 per cent of its body weight due to very high metabolic rates. It is estimated that these animals spend from 24 to 60 per cent of the day foraging.

Through his study, Estes discovered that where sea otters were lacking sea floors were filled with urchins, which had eaten all the kelp. On the contrary, where sea otters thrived, urchins lacked and kelp flourished.

Kelp forests have the capacity of absorbing huge levels of carbon dioxide, whose impact has been increasingly harming the sea as well as the atmosphere. “Our results were eye-opening,” Estes told the Guardian. “The difference in annual absorption of atmospheric carbon from kelp photosynthesis between a world with and a world without sea otters is somewhere between 13 and 43 billion kilos (13 and 43 teragrammes) of carbon,” he continued. “Every species in the coastal zone is influenced in one way or another by the ecological effects of sea otters”.

Thanks to the observation of this and other trophic cascades, Estes has contributed to highlight the huge impact that apex predators have on the shape and functioning of our ecosystems.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

Nearly 100 people have died in the heatwave in India that has badly hit millions of people who work under the blazing sun to earn their livelihood.

According to data reported by C3S, 2021 was one of the hottest years on record and Europe experienced a summer of extremes.

COP26 ended on Saturday 13th November, one day later than expected. Some positives and many negatives in the Glasgow Climate Pact, weakened by India’s last-minute change.

Governments made announcements, leaders spoke, decisions were made, civil society protested. This is what happened during the first week of COP26.

Reducing emissions means protecting our health: if unmitigated, climate change will pose increasingly severe challenges to human well-being.

The Paris Climate Agreement requires us to move towards carbon neutrality, but what does reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to zero actually mean?

If we want to limit the rise of average global temperatures to 1.5 degrees, we can emit only a limited amount of CO2. This is the carbon budget.

We talk to Shaama Sandooyea, activist and marine biologist from Mauritius onboard Greenpeace’s Arctic Sunrise ship in the heart of the Indian Ocean.

In the heart of Switzerland lies the largest glacier in the Alps, the Greater Aletsch Glacier. However, climate change is threatening its very existence.