The climate impact of the U.S. Gulf of Mexico’s oil and gas production could be higher than government inventories indicate.

Severe climate change and unpredictable weather events have caused the world’s largest man-made lake to lose more than 98% of its water.

Lake Kariba, formed by the Kariba Dam, is the largest man-made lake in the world. The double-curvature concrete dam has an estimated height of 128m with a crest length of 617m and has the capacity to hold back 181 billion cubic metres of water. The Kariba Dam was constructed across the Zambezi River between 1956 and 1959; it was commissioned in 1960 and opened by the late Queen Elizabeth II. Kariba generates an estimated 1,080 megawatts of electricity output for Zambia and 1,050 megawatts for Zimbabwe. Unfortunately, water levels have dwindled sharply in recent years, raising fears that the two nations’ hydropower turbines may have to switch off completely if water levels continue to decline.

According to data from the Zambezi River Authority (ZRA), the agency jointly controlled by the two nations’ governments, the dam had 2.34% of usable storage water, compared with 20.86% a year ago. The current water levels are close to those reached in the 1995/96 season, the lowest recorded since the 62-year-old giant dam was completed.

Zambia’s state-owned power utility company, ZESCO, which supplies energy to over 80 per cent of the country, recently announced that it would immediately increase the length of blackouts from six hours to 12 hours. Meanwhile, Zimbabweans have been forced to endure 19 hours of power outages a day. “The current water levels are extremely low at the moment. We are literally breaking new records in terms of low levels in the reservoir because the levels are lower than any recorded level in the history of a generation a the dam and this is threatening our continued electricity generation at the power station,” said Wesley Lwiindi, ZESCO Kariba North Bank Station director, in an interview.

“If the delay in rainfall were to continue much further, it could lead us to shift away from our current load management strategy, where we are managing our stakeholders, especially our high power consumers to minimise utilisation of electricity. We might be forced to move to the next level, which is load shedding in the country,” Lwiindi continued.

Meanwhile, Zambia’s President, Hakainde Hichilema, has condemned the 12-hour blackouts, saying the current load shedding had the potential to erode the economic gains Zambia has made after the Covid-19 pandemic. “I am directing ZESCO to consider splitting the 12 hours of load shedding per area into a six-hourly schedule to help maintain economic operations. We shall not shy away from taking responsibility where challenges are being faced, as that is key to addressing them. And in addressing these problems, we shall not take politically convenient, populist routes; our decisions shall be based on building sound foundations that will last for generations to come.”

Mr Hichilema said the lack of sufficient investment in the energy sector by previous governments has contributed to the perilous power deficit in the country.

“The ongoing blackouts have negatively affected my stationery business operations. I run a small business and I can’t afford alternative electricity supplies because my business solely depends on hydroelectric power for my daily operations. I don’t even know when this problem will be solved. I am extremely worried about the 12hr load shedding implemented by ZESCO. I just hope I won’t be forced to go out of business. How long I can hold on, only God knows,” said Joseph Mwenda, a businessman based in Isoka, Zambia.

“My life depends on this business, but now it is just a shadow of its former self. No one comes to access printing and cyber services because I do not have electricity. I think the weeks ahead will be rough,” said Mwenda.

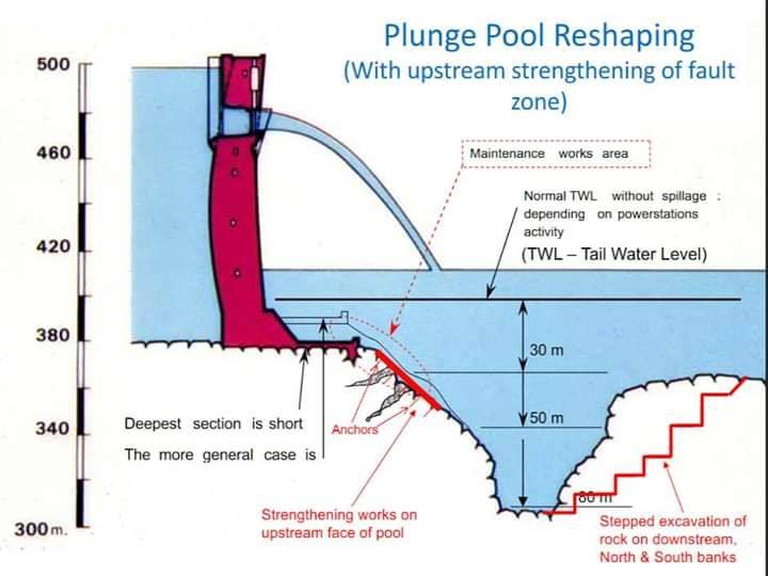

Meanwhile, after more than 50 years of generating power for the Southern African region, the Kariba Dam is currently going through rehabilitation works for its continued safe operation. The renovation works involve reshaping the plunge pool to limit scouring and erosion coupled with the refurbishment of the spillway and associated infrastructure to improve the dam’s stability and future operations.

For nearly a decade, experts have raised concerns regarding the dam’s lack of structural maintenance and negligence. Unfortunately, the dam’s torrent spillage has excavated a giant cavern in the Zambezi river bed, now the cavern has grown to more than 10 times bigger and deeper than the original design dimensions and it is threatening the stability of the foundations of the dam structure.

Some energy experts have suggested that the Congo River in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the continent’s second longest, could hold the solution for the Zambezi River’s water scarcity. “We are strongly advising the Zambian government to consider digging a canal that can direct water from the Congo River to the source of the Zambezi. This development will improve electricity generation for both countries.”

But Arthur Chapman, an independent consultant in climate change adaptation and disaster risk assessment remains pessimistic. “Even if the heads of state of Zambia, DRC and Zimbabwe agree to the canal idea, the plan will never be achieved, due to the fact that the Zambezi’s source lies in the far north-west corner of Zambia, more than 100km from the Congo River.”

Considering the current electricity deficit the two drought-stricken countries are experiencing, they should look to renewable energy for a reliable, efficient and sustainable energy supply.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

The climate impact of the U.S. Gulf of Mexico’s oil and gas production could be higher than government inventories indicate.

ReconAfrica hunt for oil and gas threatens vital waterways home to the world’s largest elephant population and endangered wildlife

Despite environmental warnings, the Tanzanian government is set to build a dam in the heart of the Selous Game Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Researchers from the IFM at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia have tested a novel method for removing silicon from used solar panels.

The Congolese government is allowing energy firms to bid for access to its vast oil and gas reserves, risking terrible ecological and climate effects.

The US government has approved ConocoPhillips’s controversial Willow Project to drill for oil in Alaska’s National Petroleum Reserve.

Environmental activists say the EACOP pipeline will damage Uganda’s iconic fragile ecosystem and the livelihoods of tens of thousands of people.

The EU has banned the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans from 2035. From then on, new cars and vans sold in the EU must run on other fuels.

Environmental activists have accused Eskom of emitting toxic chemicals that are costing thousands of lives and changing rainfall patterns.